Editorial: How many nurses does it take to change a patient’s blood?

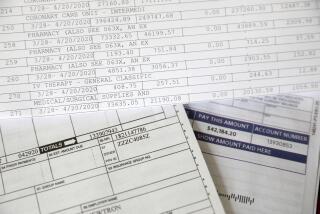

One in seven Americans suffers from chronic kidney disease, usually as a toxic byproduct of diabetes or high blood pressure. Almost half a million people across the country, including more than 60,000 in California, have conditions so severe that they require dialysis three times a week or a new kidney to stay alive. Caring for each of those patients costs a whopping $89,000 a year on average, most of which is paid by taxpayers through Medicare and Medicaid.

The rising demand for dialysis has led to a boom in outpatient clinics that specialize in it. Two companies in particular — DaVita, which operates 286 dialysis centers in California, and Fresenius Medical Care, which operates 127 — have captured 70% of the market nationally, turning the decline in kidney health into billions of dollars in annual profits.

Those centers and their profits are now the subject of a pitched battle in Sacramento over proposals to supplement federal regulations on the centers with new state requirements. Unfortunately, the proposals would raise the cost of dialysis without necessarily improving it.

Dialysis providers are overseen by the federal government, whose rules are enforced mainly by state health regulators and 18 regional panels that monitor the quality of care. Some state lawmakers argue that the dialysis clinics popping up in mini-malls across their districts need more specific mandates, and they are advancing a pair of bills to impose them.

Measuring the number of nurses and technicians in a building ... isn’t the same as measuring the quality of care.

SB 349 by Sen. Ricardo Lara (D-Bell Gardens), cosponsored by the California branches of the Service Employees International Union and the United Nurses Assns., would set a minimum number of nurses, technicians, dietitians and social workers that dialysis centers would have to employ per patient treated, including one nurse on duty for every eight patients and one technician on duty for every three patients at all times. It would also mandate a 45-minute gap between patients receiving dialysis, while requiring the state to inspect each center at least once per year.

As unusually prescriptive as Lara’s bill is, a second measure would take an even more extreme step. Also sponsored by SEIU, AB 251 by Rob Bonta (D-Alameda), would require dialysis centers to spend 85% of their revenue on patient treatment. Although federal law imposes a similar limit on health insurers, there are no such profit caps on healthcare providers.

(SEIU-United Healthcare Workers recently filed initiatives to put the elements of one or both bills before state voters in 2018. No surprise there — the union has repeatedly used legislation and ballot measures to pressure hospital chains as it tried to organize their workforces.)

Research has shown that treatment problems tend to be more common at nursing homes and other healthcare facilities with a higher ratio of patients to caregivers. Perhaps that’s why eight other states have set minimum staffing ratios for their dialysis centers. But supporters of the Lara bill offer no evidence to show centers in those states have better safety and quality records than the ones in California do, or to support the specific ratios and time limits they’re advocating.

Minimum staffing ratios may be appealing because it’s easy to tell when a center isn’t complying. But measuring the number of nurses and technicians in a building, like tallying profit margins or counting the minutes between patients, isn’t the same as measuring the quality of care. There are far better ways to do that — for example, by tracking the number of infections linked to a center’s equipment.

To hold down costs and improve quality, policymakers across the country have sought to give healthcare providers more incentives to deliver better care more efficiently. The Lara bill steers in a very different direction, proposing rules that would make costly dialysis treatment even more expensive without trying to incentivize or measure any improvement in care.

The Lara bill also could reduce the availability of dialysis in some communities, if centers decide to treat fewer patients and keep more limited hours rather than hire the extra personnel. That seems a particular risk for the many smaller companies operating in the shadow of DaVita and Fresenius. So while patients could be helped by the added inspections and staff, they may find treatment harder to obtain.

The state Department of Public Health receives roughly 200 complaints a year about dialysis centers, so it’s reasonable to demand better performance. But a study by UC Davis in 2013 suggests that better enforcement of federal regulations would be the right way to address the centers’ shortcomings, not layering on state requirements that don’t directly improve care quality. Lawmakers ordered that study. They ought to heed its findings.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.