Trail users cite safety, hygiene concerns with transient squatters at Gould Mesa campground

Altadena Town Councilwoman Dorothy Wong has long visited the Gabrielino Trail, northeast of La Cañada’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, hiking and biking up to its Gould Mesa Trail Camp for nearly two decades.

But like many area hikers and equestrians who frequent the area, she’s begun to notice an influx of people who seem to be using the Angeles National Forest for purposes more residential than recreational.

“I always saw it as a place for recreation and camping,” Wong said of the area. “[But] within these past five years or less there are people coming in who are clearly homeless and trying to live there.”

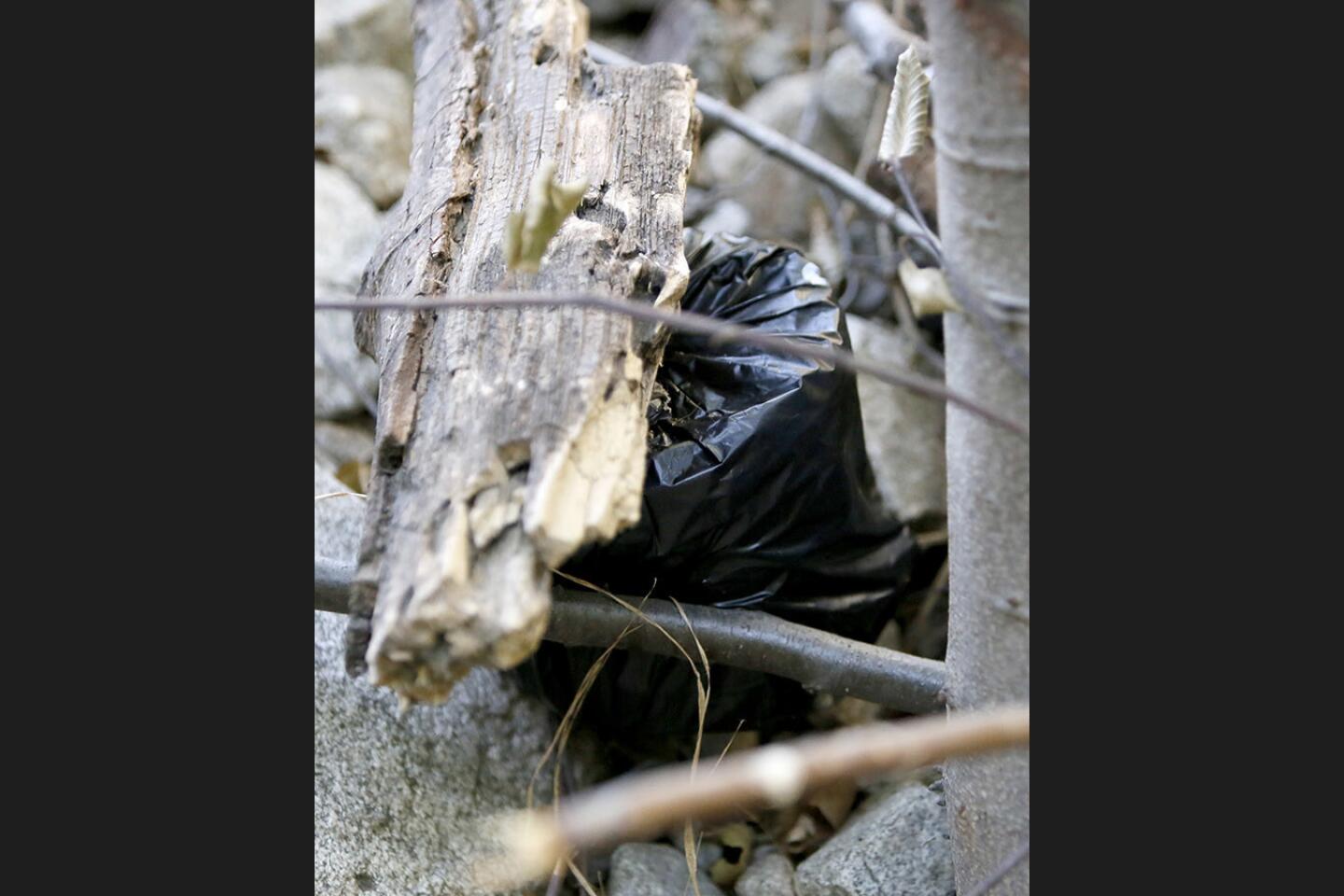

Recent social media from residents and volunteer groups detail encounters with apparent squatters, who set up tents long term and leave trash and the ashes of illegal fires in their wake.

In June, deputies with the Crescenta Valley Sheriff’s Station responded to a call from hikers who said vagrants in a makeshift encampment near the Gould Mesa campground confronted them with knives and machetes. By the time authorities arrived on scene, the camp had been vacated.

Nancy Rose lives in El Monte and boards her horse at the Rose Bowl Riders club in Hahamongna Watershed Park. She said she’s stopped using the Gabrielino Trail.

“I don’t feel safe anymore,” she said, describing fires, human feces and untethered dogs that spook horses. “It’s really not fair to the public to have something like that happening — and nobody’s doing anything.”

Title 36 of the Code of Federal Regulations, which governs use of parks and forests, prohibits camping outside designated areas and the installation of permanent camping facilities. It states people may not leave camping equipment, site alterations or refuse behind when they leave.

Angeles National Forest campgrounds impose a 14-day stay limit per trip and cap campers at 30 days per year. But such rules can be difficult to enforce, given the area’s complicated jurisdictional boundaries.

Northern portions of the Arroyo Seco, for which the city of Pasadena has water rights, run into the Angeles National Forest, monitored by the U.S. Forest Service. Some of its acreage is under the law enforcement authority of the Crescenta Valley Sheriff’s Station.

Geographically, La Cañada Flintridge residents can approach the Upper Arroyo Seco from a fire road off Angeles Crest Highway to the west, while the area is bordered to the southeast by Altadena, part of unincorporated Los Angeles County.

Wong says the jurisdictional jumble makes it hard for agencies to coordinate a response when recreating citizens run up against illegal campers and the messes they leave behind.

Altadena father Gerard Shadrick visits the Gabrielino Trail with 9-year-old daughter Talulah, who likes to catch tadpoles in nearby creeks. Last weekend, the pair found a plucked chicken carcass with its head floating in the stream, while two dozen smashed raw eggs surrounded the area. Nearby, glass prayer candles glowed in one of several burn spots still littered with smudged rolls of tobacco.

Revisiting the scene Tuesday, they found the candles had been re-lit.

“This is not cool,” Shadrick said. “My daughter plays in that stream, and so do all these other kids. It’s a public health issue.”

Officials with the U.S. Forest Service turned down a request for an interview, instead offering a statement from Jamahl Butler, acting district ranger for the Los Angeles River Ranger District.

“The Angeles National Forest is aware of issues related to unauthorized occupancy of federal lands at Gould Mesa. We are working with our partner agencies to develop effective strategies to address these issues,” read the statement. “The Forest Service remains committed to resource protection and public safety consistent with our mission and available resources.”

Butler refused to name which agencies the Forest Service has been working with in response to resident complaints about the Gould Mesa Trail campground and Gabrielino Trail.

Wong said she recognizes the clash between recreational users and forest dwellers as one more manifestation of Los Angeles County’s growing homeless population and believes a solution must be broad to be effective.

“The situation is bigger than just kicking people out,” she reckoned. “We have to do something and that something is not easy, whatever it is.”

Twitter: @SaraCardine