In 2021, the complicated lives of Black music legends power Oscar’s acting noms

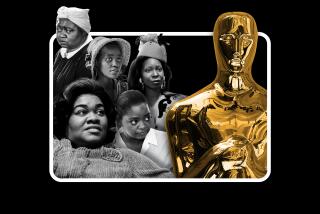

When Viola Davis and Andra Day face off for the lead actress trophy at Sunday’s 93rd Academy Awards, the competition will mark just the second time that two Black women have been nominated in that category in the same year.

That’s not the only bit of Oscars history they’ll be making nearly half a century after Diana Ross and Cicely Tyson both received nods in 1973. For the first time at the Academy Awards, the performances nominated for lead actress include two portrayals of famous real-life musicians: the pioneering blues singer Ma Rainey (as played by Davis in “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom”) and the legendary jazz vocalist Billie Holiday (as played by Day in “The United States vs. Billie Holiday”).

The men’s categories are crowded with music too. In supporting actor, Leslie Odom Jr. is up for his role as yet another real-life star, gospel and soul great Sam Cooke, in “One Night in Miami…” Add the two actors tapped for their lead performances as fictional characters — the late Chadwick Boseman’s jazz trumpeter in “Ma Rainey” and Riz Ahmed’s drummer experiencing hearing loss in “Sound of Metal” — and fully a quarter of the nominations for Hollywood’s highest acting honors recognize depictions of musicians.

Oscar voters have long been drawn to stories about folks who win Grammys, of course — think “Walk the Line” and “Ray” and “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” Pop stars’ colorful lives contain built-in drama, while names like Johnny Cash and Ray Charles and Loretta Lynn promise built-in audiences.

On the fifth anniversary of his death, we rank every Prince song officially released as a single, from 1978’s ‘Soft and Wet’ to 2015’s ‘Free Urself.’

Yet this year’s field stands out not just for the unusually high number of music-related nominations but for the types of music involved. In 2019, voters showered nominations on “Bohemian Rhapsody,” about the classic rock band Queen, and on Lady Gaga’s roots-rock reboot of “A Star Is Born”; last year Reneé Zellweger was named best actress for playing Judy Garland and Elton John won an Oscar for original song for a tune he wrote for his own biopic.

Black music, in contrast, is at the heart of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” and “The United States vs. Billie Holiday” and “One Night in Miami…” — and of “Soul,” the Pixar film about a jazz pianist that’s nominated in the animated feature category.

In addition to Odom’s acting nod, “One Night in Miami…” earned an adapted screenplay nomination for Kemp Powers, who also co-wrote and co-directed “Soul”; the original song and original score categories are equally filled with jazz and R&B by composers and performers including Terence Blanchard (“Da 5 Bloods”), H.E.R. (“Judas and the Black Messiah”) and Jon Batiste (“Soul”).

Look beyond the Oscars and you’ll find even more stories about Black music in film and television: National Geographic’s miniseries “Genius: Aretha,” about Aretha Franklin; HBO’s “Tina,” about Tina Turner; “Sylvie’s Love,” the Amazon Studios movie about two young lovers in Harlem’s early-’60s jazz scene; and director Steve McQueen’s “Small Axe” anthology, including the reggae-drenched “Lovers Rock.”

Why? Hollywood would say this is the fruit of its efforts to expand representation in the wake of Black Lives Matter and #OscarsSoWhite. That may certainly be true, though one can’t discount the fact that the labor of diversity has been made easier with the creation of a zillion new streaming services that require less investment of resources than the old theatrical business. (We’ll see how much energy studios continue to put into projects like these after COVID relinquishes its grip on a captive audience.)

Even assuming the best of the industry, it’s worth noting that there’s an essential small-C conservatism at work here: Jazz and soul music and reggae are long-established forms with which Hollywood has no real choice but to feel comfortable at this point. One more recent movie about Black music — actor-writer-director Radha Blank’s moving and hilarious “The 40-Year-Old Version,” in which she plays a struggling playwright who reinvents herself as a rapper — earned rave reviews and fared well on the festival circuit.

Alas, it’s set in the world of hip-hop, which helps explain why Blank isn’t in the Oscars mix.

Though it vividly depicts an artist’s creative frustrations, “The 40-Year-Old Version” is also short on the kind of personal trauma that the academy tends to overvalue in nominated performances, particularly in portrayals of musicians’ lives. Suffering is a big part of what we see Davis’ and Day’s characters do in “Ma Rainey” and “Billie Holiday”; it’s central to the experience Ahmed dramatizes in “Sound of Metal.” To be sure, all three performers bring a sensitivity to their roles that preserves each character’s humanity. But presenting musicians as fundamentally tortured is a move as limiting as it is familiar.

If the talent celebrated Sunday suggests that Hollywood is thinking more widely about whose musical stories to tell, maybe next the movies can broaden how exactly they’re told.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.