Review: Dudamel channels American cowboys, indigenous Mexicans, ethnic groups of South America

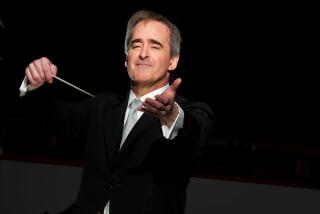

Neither in his native Spanish nor in the English in which he has become fluent during his decade as music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic does Gustavo Dudamel accept the singular “America” into his vocabulary. There is only Américas or Americas. For this Venezuelan conductor, we are, from the Canadian Yukon to the southernmost reaches of Argentina and Chile, one.

He proclaimed as much at the free Hollywood Bowl event dedicated to all of Los Angeles in 2009, his first concert as music director. He has led multiple festivals of the Americas, celebrating the concert, folk, pop and jazz musics of the continents north and south. Last week he began his 11th L.A. Phil season and the orchestra’s 101st with yet another, this time a two-part look at our contingent continents from the vantage of Walt Disney Concert Hall.

The previous program happened to concentrate on the U.S. with works by Barber, Gershwin, Previn and Copland written in New York and with an unusually narrow thematic focus on the Big Apple, Nashville and Appalachia. Thursday, for Part Two (repeating through Sunday), Dudamel moseyed a bit farther west and a lot farther south.

He looked at our myths and our folklore. He paid more attention to Copland with a winning performance of “Rodeo” of such spectacular vitality and character that he left even the bronco-bucking Leonard Bernstein in the dust. It was a cowboy epiphany, to be sure, Copland like he’s never been heard before.

But the revelation came in Carlos Chávez with a performance of “Sinfonía India,” the Mexican composer’s second symphony, which preceded the world premiere of Argentine composer Esteban Benzecry’s blistering Piano Concerto, “Universos Infinitos.” Mexico proved the convincing center of it all.

We pay far too little attention to Chávez, notwithstanding Southwest Chamber Music having surveyed and recorded his music years ago. His influence on the music of the Americas is crucial. He and Copland were born a year apart (1899 and 1900, respectively) and became close friends in New York, where Chávez spent part of the 1930s, and in Mexico, where Copland visited often. Like Chávez, Copland had periods as a modernist and populist — the latter begun, not coincidentally, with “El Salón México,” inspired by a dance hall Chávez took him to in Mexico City.

Chávez, moreover, happened to throw critical support into the founding of El Sistema, the education program in Venezuela that gave us Dudamel. There is a strong West Coast connection as well: Chávez was a friend to and an influence on Lou Harrison and took part in the early years of Harrison’s Cabrillo Festival in and around Santa Cruz.

“Sinfonía India,” an irresistible 11-minute score from 1936 based on folk material, including a lyrical Yaqui melody from Sonora of such ravishing beauty that once you hear it, you’ll never forget it. It is Chávez’s best-known score (Alfred Wallenstein conducted with the L.A. Phil in 1952). The rhythmic energy is motoric; meters are Stravinskyan in their complexity. But only Chávez gets the flutes to flutter like birds.

Though an experienced conductor, Chávez makes a mess of it in his recording. It’s long been a party piece of Dudamel’s, but it somehow took a decade for him to conduct it here, and he made it sizzle.

Like Chávez, Benzecry, who was born in 1970, is obsessed with ancient Latin American civilizations, their myths and musics, and his “Universos Infinitos” has to be the first piano concerto ever written around the planetary and agricultural cycles that regulated indigenous Americans. Plus, just as Chávez and Copland got much of their technique from Parisian modernism, so too Benzecry.

The concerto, which was written in 2011 but only now is receiving its first performance, has an ambitious programmatic reach. The bravura first movement, the composer writes in his notes, is “subjected to cosmic, atmospheric, agricultural, etc. avatars, with its eternal flux and alternation of situations happy and unhappy.” And that’s only the first theme.

In the nocturnal middle movement, “Nuke Kuyen” (Mother Moon), a melody from the M,apuches of southern Chile and Argentina (who believe themselves descended from stardust) becomes transformed into eerie microtones. The knock-’em-dead toccata that ends the concerto represents a festive winter solstice gathering of Guarani ethnic groups who cover vast swaths of South America.

The concerto is dedicated to the virtuoso Venezuelan pianist Sergio Tiempo, who played it from memory, which seemed an impossibility. A catapulting Tiempo almost never stops for 30 minutes. The Steinway is subject to all you might ever want to subject it to. Phenomenal runs. Tone clusters banged out with the elbows. Percussive playing of the strings inside the instrument. Tiempo somehow made the impossible possible.

Dudamel introduced “Rodeo” with Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man,” with nothing common about it. Any barely capable conductor can get away with “conducting” this (take it from me). But somehow Dudamel made an introductory stroke of timpani gong sound like a universal call of all peoples from all places. The L.A. Phil brass is in the best shape it has ever been in. It was just what the common man and woman needs in this country at this time — again, the impossible possible?

He then chose to conduct the rarely heard full “Rodeo” ballet score rather than the usual “4 Dance Episodes” concert version. The main difference is the inclusion in the middle of “Ranch House Party,” with its honky-tonk piano. There is a commercial video of Copland conducting the last part of the ballet, “Hoe-Down,” with the L.A. Phil. It sounds like good-natured, slightly highbrow cowboy music. Copland never liked too much emotion.

Others have found more in the ballet. The rhythms jerk and leap like a wild horse. The nocturnal episode has a tint of the mystical. I’ve followed Copland performance over the years and know all the recordings. Dudamel went deeper into it than any before him. He also had more fun on the surface.

It was an astonishing performance by the L.A. Phil. Instrumental solos leaped to life, so many so that Dudamel became amusingly flustered at the curtain call trying to remember everyone to acknowledge for a hand. The brass in toto deserved a medal.

A performance of “Rodeo” isn’t supposed to be one of the year’s life-affirming highlights. I know this is tiresome already, but by “Hoe-Down”-time, another impossibility bit a certain Venezuelan cowpoke’s bullet.

'Dudamel Conducts Music From the Americas'

Where: Walt Disney Concert Hall, 111 S. Grand Ave., L.A.

When: 8 p.m. Friday-Saturday, 2 p.m. Sunday

Tickets: $72-$220

Info: (213) 850-2000, www.laphil.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.