Bruce Springsteen, Morgan Wallen and the myth of unity

During the Super Bowl on Sunday night, a squinting, papery-voiced Bruce Springsteen took part in what Boss-ologists have said was his first television commercial: a two-minute Jeep spot, called “The Middle,” in which the singer, clearly inspired by the long-awaited end of the Trump era, waxes poetic about the philosophical importance of the middle as he tools around a small town in Kansas that sits at the geographical center of the mainland United States.

“It’s no secret,” he says over the plaintive whine of a steel guitar. “The middle has been a hard place to get to lately — between red and blue, between servant and citizen, between our freedom and our fear.” Then, as we see him running his hands through the frozen heartland dirt, he tells us, “We just have to remember the very soil we stand on is common ground.”

Springsteen’s high-flown pitch wasn’t the only gesture toward unity at a closely watched sports extravaganza that came one month and a day after the storming of the Capitol by pro-Trump extremists.

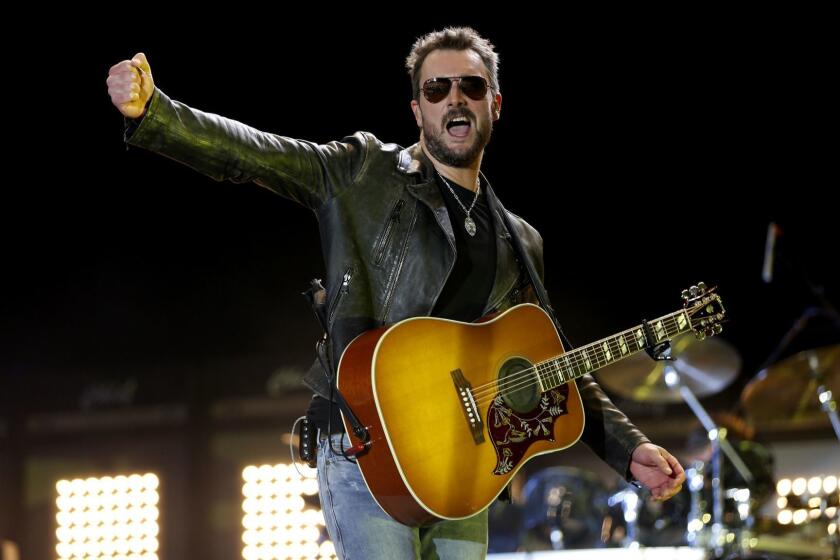

Before the game, in an unlikely pairing arranged by Jay-Z’s Roc Nation firm, the national anthem was performed by the country star Eric Church and the R&B singer Jazmine Sullivan — a duet that Church (one of whose biggest hits is called “Springsteen”) recently told me he agreed to as a direct response to the Capitol riot.

“I’ve avoided it forever,” he said of the notoriously difficult-to-sing anthem. Yet watching the events of Jan. 6 led him to reconsider: “With what’s going on in America, it feels like an important time for a patriotic moment. An important time for unity. The fact that I’m a Caucasian country singer and she’s an African American R&B singer — I think the country needs that.”

On Sunday, Eric Church will perform the anthem with R&B singer Jazmine Sullivan. “We’re unifying. And it’s a time in our country when we have to do that.”

Yet the reaction to both Springsteen’s commercial and to Church and Sullivan’s “Star-Spangled Banner” — in a broadcast, it’s worth remembering, presented by a league that essentially blacklisted Colin Kaepernick because he knelt during the anthem — raises complicated questions about exactly what this vaunted unity looks like and precisely whose labor it requires.

As with any rich celebrity who urges Americans to fix problems from which the celebrity is largely shielded, the Boss’ entreaty triggered the expected eye-rolling on social media. Some conservative pundits pointed out that Springsteen, an enthusiastic Democratic activist who supported Joe Biden in the bruising 2020 election, was calling for a truce only after his guy beat Trump; many progressives were bummed that he was shilling for a pollution-spewing car company.

More interesting were the tweets I saw in response to the performance by Church and Sullivan, many of which boiled down to: Why did a Black woman as talented as Sullivan have to share her big moment with a white man?

“Now they know good and damn well they should have let Jazmine Sullivan sing the national anthem by her got damn self,” wrote Shea Couleé, a former contestant on “RuPaul’s Drag Race.”

The practical answer is that Sullivan, a magnificent singer and storyteller, simply lacks the widespread recognition that the NFL has historically sought in a solo performer. (So, for that matter, does Church.) In recent years, the anthem has been sung by the likes of Lady Gaga, Pink and Gladys Knight; together, as Roc Nation clearly understood, Sullivan and Church represented an intriguing draw to rival those household names.

But the righteous exasperation over Sullivan’s being asked, like so many Black women before her, to accommodate someone else made me think about the reaction to a country-music controversy that was almost certainly in Church’s mind as he enacted his vision of racial reconciliation on Sunday: Morgan Wallen’s use of the N-word as caught on video last week and published by TMZ.

As an industry, Nashville was unusually swift to condemn Wallen’s behavior, which took place in his driveway as he returned home “from a rowdy night with friends,” as TMZ put it. His record label announced that it had “suspended” the singer’s contract (whatever that means), while radio conglomerates said they were taking Wallen’s music off the air and trade groups said they would exclude him from awards consideration.

Radio companies and streaming services swiftly rebuked Morgan Wallen for using a racial slur, but Wallen is just a symptom of a larger problem in country music.

Yet many fans quickly rallied to Wallen’s side on social media — and not only there. On Sunday, Billboard reported that sales and streams of the singer’s album “Dangerous” had gone up 14% in the preceding seven days, enough to keep the LP atop the Billboard 200 chart for a fourth consecutive week.

Attitudes varied among those voicing support for Wallen. Some said he’d made an out-of-character mistake and deserved a second chance, as Rakiyah Marshall, a Nashville exec involved romantically with the CEO of Wallen’s label, argued in a widely discussed Instagram post.

“I’m not giving up on him,” wrote Marshall, who is Black, next to a photo of herself with her arm around Wallen’s neck. “Hope the world gets to see the person I know in that picture.”

Others, though, identified the singer as the latest victim of so-called cancel culture and wondered (or pretended to wonder) why he’s not allowed to use the N-word when countless rappers are.

I’m not equating ride-or-die Wallen fans willing to follow him anywhere with Sullivan fans who view Church’s well-intentioned Super Bowl involvement as just another product of white privilege. But as embodiments of racist and anti-racist thinking, respectively, both flank a supposed moral center that feels increasingly inadequate to those outside the ‘60s-liberal bubble that Springsteen (and President Biden) occupy.

Could anyone watch this Jeep ad and be genuinely moved — not by its sweeping aesthetics but by its childish political proposition?

The most aggrieved of Wallen’s fans don’t want to live in Springsteen’s middle because it’s a place where old hierarchies are challenged and you can’t say what you want without consequence. And few of Sullivan’s fans are rushing to get there because to do so is to be expected to forgive too much in the name of unity.

Of course Springsteen’s American utopia is a thing to be longed for — a thing you could even let yourself believe in a little as you listened to Sullivan use her miraculous voice to celebrate a country that for centuries has made life harder than it needs to be for Black people.

But at a moment when Trump’s acolytes in government are saying it’s time to move on already from the insurrection, it’s disappointing that rock’s great champion of the dispossessed can’t see that progress requires more work by some than by others.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.