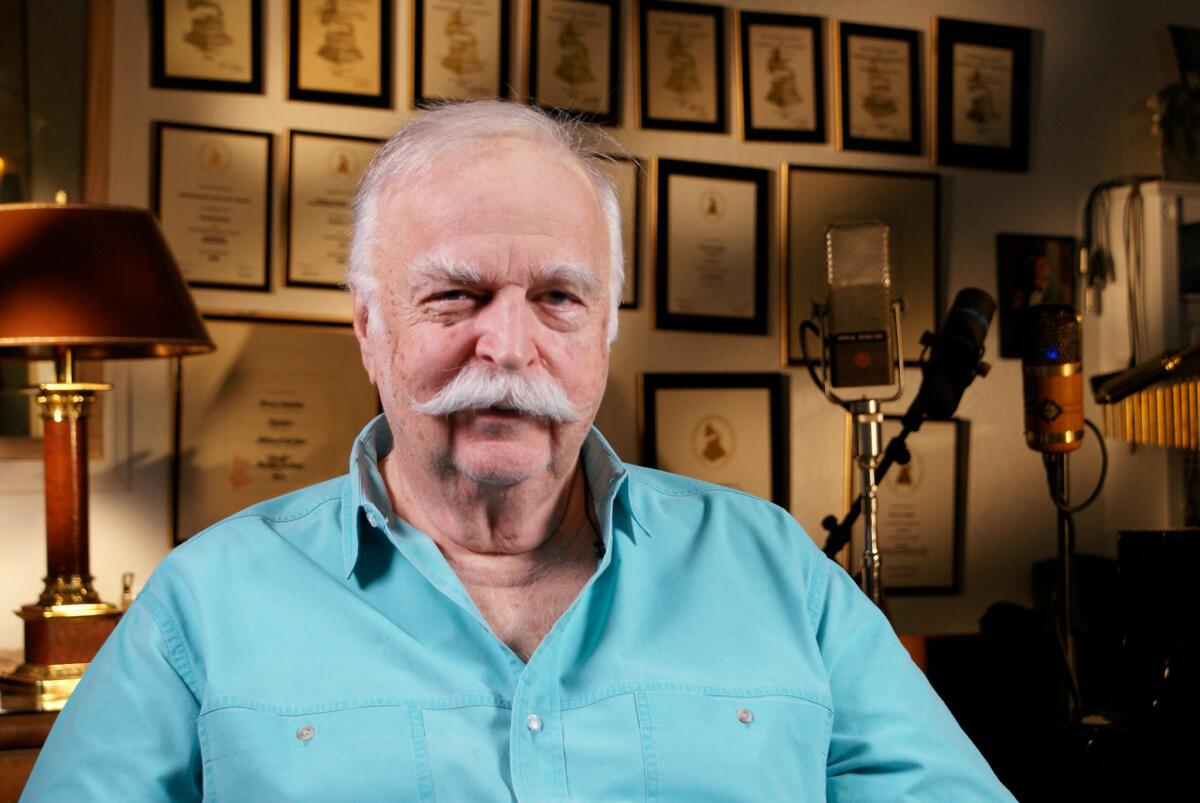

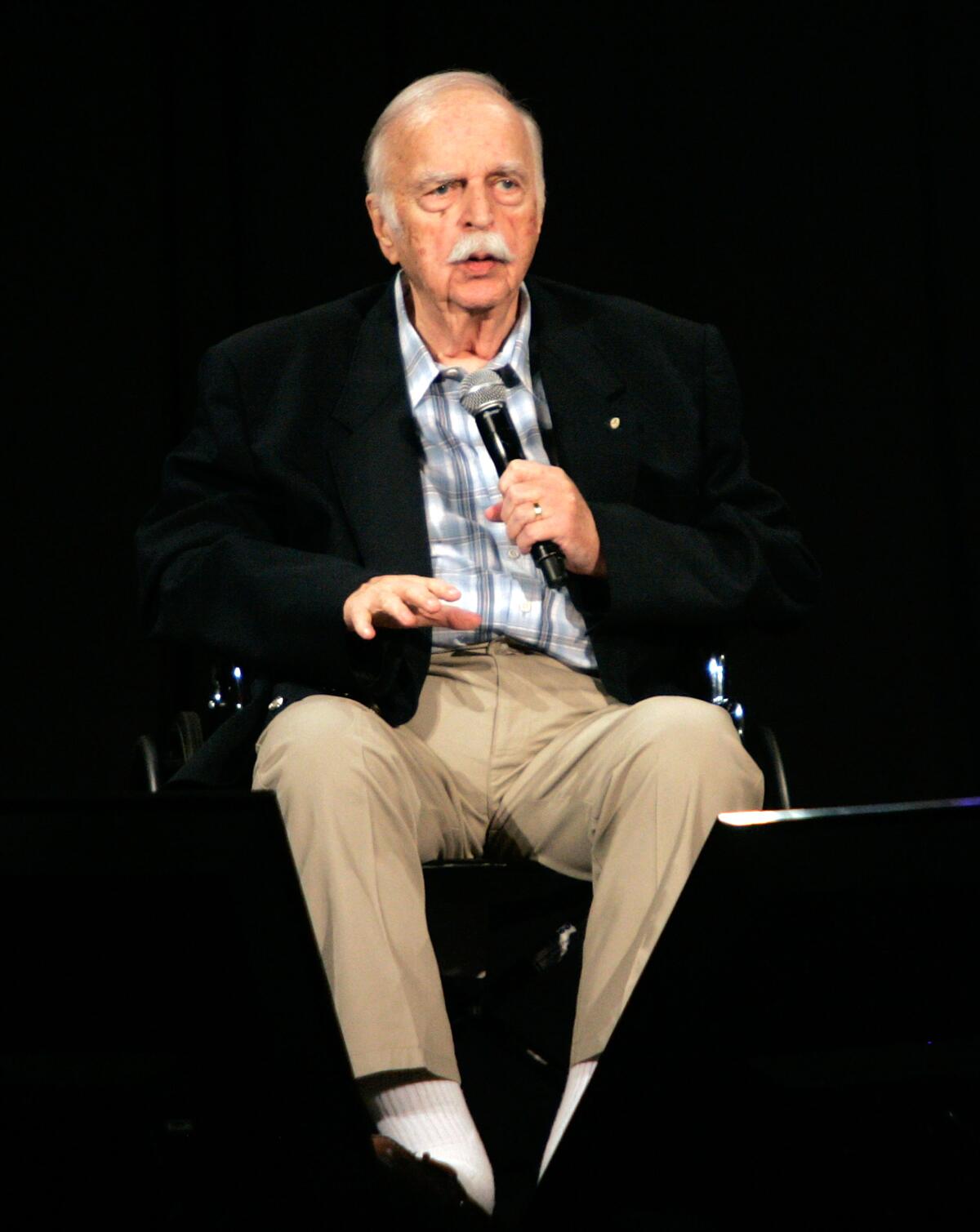

Bruce Swedien, award-winning engineer for Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller,’ dies at 86

Recording engineer Bruce Swedien, whose Grammy-winning work in the studio with Quincy Jones on Michael Jackson’s classic solo albums “Off the Wall,” “Thriller” and “Bad” helped define the sound of pop music in the 1980s and beyond, has died. He was 86.

“He was without question the absolute best engineer in the business,” wrote his longtime studio partner, Quincy Jones, adding that “for more than 70 years I wouldn’t even think about going into a recording session unless I knew Bruce was behind the board.”

His death was announced by his daughter, Roberta Swedien, who wrote on Facebook that her father “passed away peacefully” on Monday night in Gainesville, Fla. after a long illness and complications from surgery.

Is the birth of the Los Angeles recording industry nestled in the grooves of these newly discovered wax cylinders?

Swedien’s daughter described him as a “legend in the music industry for over 65 years,” and across those decades he channeled a childhood obsession with the art and science of capturing sound on tape to create magic. Swedien engineered crucial jazz and soul records by artists including the Ramsey Lewis Trio, the Rev. Cleophus Robinson, the Chi-Lites, Herbie Hancock, and Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. As his career blossomed, he worked with artists including Barbra Streisand, Chaka Khan, Donna Summer, Jennifer Lopez, Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger and Roberta Flack.

As a producer, Swedien oversaw New Edition’s 1986 hit “Once in a Lifetime Groove,” a number of solo albums by Doobie Bros. singer Michael McDonald, much of actor David Hasselhoff’s musical oeuvre, and Rene and Angela’s “Your Smile.”

But it is his groundbreaking engineering work for Quincy Jones and Michael Jackson that Swedien is best known for. When Swedien met Jones, both were in their early 20s and could spot a kindred spirit, Swedien recalled. After a few sessions, it was evident “that Quincy and I could make beautiful music together because we liked each other a lot. We think alike and our tastes are alike.” The two went on to make records with major jazz artists including Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Dinah Washington and Sarah Vaughan.

The two took separate paths in the early 1970s — Jones moved to Paris — but reconnected in 1975 to collaborate on albums for the Brothers Johnson, George Benson and Lesley Gore. When Jones accepted the job making Jackson’s 1979 debut solo album, “Off the Wall,” Swedien was part of the package. The engineer recalled being astounded by Jackson’s talent, as well as his eagerness to experiment.

In his Instagram statement, Jones heaped praise on Swedien’s way in the studio during the “Thriller” sessions: “I have always said it’s no accident that more than four decades later no matter where I go in the world, in every club, like clockwork at the witching hour you hear ‘Billie Jean,’ ‘Beat It,’ ‘Wanna Be Starting Something,’ & ‘Thriller’. That was the sonic genius of Bruce Swedien.”

To record drums on Jackson’s “Rock with You,” for example, the engineer built a heavy-duty drum platform that was braced and counter-braced about a foot above the ground. Made of unvarnished, unpainted wood, it helped drummer J.R. Robinson capture the specific thump that propels the song.

For Jackson’s backing vocals on songs from “Thriller,” Swedien suggested that the singer record a pair of similar takes a few inches from the microphone, step two paces back to record another take and then record another as Jackson moved his mouth and voice across the microphone to create a kind of stereo pan. Swedien then layered the tracks to create a Jackson choir. The combined effect, Swedien wrote in his book “Recording Michael Jackson,” tricked the ear into perceiving depth of field.

Such inventiveness expanded the potential of the studio and was learned through countless hours in windowless rooms focusing solely on vibrations and frequencies.

That a teenage Swedien was destined to work in recording studios was so obvious to his parents in post-war Minneapolis that when visiting Chicago in the mid-1950s, they sought out one of their son’s idols, the recording pioneer Bill Putnam. Putnam told them that if their son ever moved to Chicago he’d give him a job at his Universal Recording Studios. Soon Swedien was overseeing the facility’s studio B. After Putnam relocated to Los Angeles at the behest of Frank Sinatra to open United Western Recorders, Swedien took over in Chicago.

“I learned microphone technique by experimenting with Count Basie, with Woody Herman, Duke Ellington [and] Stan Kenton,” Swedien explained of his time at Universal. “[They] were so fascinated by the recording technique and would put up with me trying to experiment with different sounds and different microphones.”

Swedien recalled all-night sessions with Basie and his band that didn’t begin until the clubs had closed. Musicians rolled in, each with a few friends until the recording studio was part session, part party. But then, said the engineer, “Count Basie would stand up to give the down beat, and boy that tape would better be rolling.” When that happened, the crowd stopped. “They all sat down and did not make a sound. It was magic. ... You can feel the electricity in the room.”

In an interview with a recording industry trade group, Swedien recalled a tip Jones once gave to him: “Don’t be after your time and don’t be before your time. Be right on time.”

In addition to his daughters, Roberta Swedien and Julie (Loren) Johnson, Swedien is survived by his wife of 67 years, Bea.

More to Read

Updates

10:44 a.m. Nov. 18, 2020: Updated to include further information on Swedien’s recording career and familial survivors.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.