Review: How Beyoncé changed Coachella’s temperature

So much for the “white people stage.”

That’s how Vince Staples, the deeply skeptical Long Beach rapper, referred to the main stage of the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival as he found himself performing — with one eyebrow cocked in surprise — on just that platform Friday night.

And he was hardly being unfair: Since its founding in 1999, the annual multi-day event in Indio, which is widely regarded as the country’s most prestigious music festival, has generally privileged rock and dance-music acts such as Radiohead, Paul McCartney and Calvin Harris; in turn, the show has developed a loyal audience known, if somewhat less accurately, as a congregation of rich white kids.

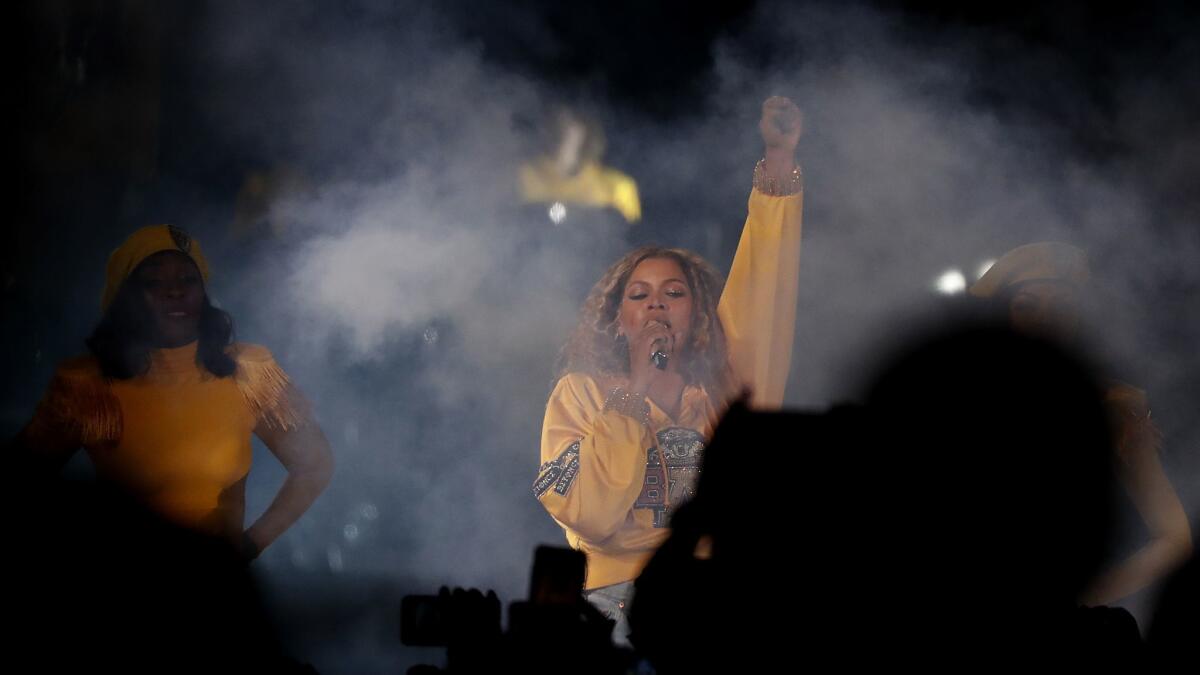

Yet just over 24 hours after Staples’ pronouncement, Beyoncé replaced him in Coachella’s spotlight to deliver the most radical — and maybe the best — headlining performance I’ve ever seen here: a thrilling and painstaking tribute to America’s historically black colleges and universities that had the singer leading approximately 100 musicians and dancers, including brass and string players, a drum line, a baton twirler and even a lively step squad that went to work when she left the stage to change costumes.

At one point, a voice booming over the festival’s sound system described the concert as Beyoncé’s “homecoming,” even though this was her debut at Coachella, and one that made her the first black woman to headline the festival. (“Ain’t that ‘bout a bitch,” she added in a pitch-perfect aside.)

That nobody in the crowd seemed to object demonstrated how completely she was making the place her own.

The thoroughness of the presentation, with skits and long dance routines and radical rearrangements of some of Beyoncé’s best-known songs, was staggering — miles beyond what even the most ambitious of Coachella’s other performers are bringing to the desert.

“Freedom,” riding a heavy groove played on sousaphones, suddenly morphed into a rendition of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often called the black national anthem. “Sorry” sprouted a hilarious and salty call-and-response chant that can’t be printed here. “Drunk in Love,” which Beyoncé sang from atop a rotating cherry picker, sounded as woozily festive as New Orleans funeral music.

Saturday’s triumph by the 36-year-old pop superstar — who said she’d been planning the spectacle since 2017, when she bailed on an earlier booking at Coachella after announcing she was pregnant with twins — signified a larger trend at this year’s festival, held Friday to Sunday at Indio’s Empire Polo Club and due to repeat next weekend with the same lineup.

Instead of the rock bands of yore, Coachella’s most prominent acts — which include the Weeknd, SZA, Cardi B, Migos and Eminem, who was scheduled to headline the festival Sunday evening — come out of hip-hop and R&B. The bill isn’t entirely free of the guys with guitars whom Staples may have been thinking of during his time on the enormous main stage.

But to the extent that a festival as big as this one can tell a unified story, rock bands like Fleet Foxes and the War on Drugs didn’t feel like part of it, at least not during Weekend 1.

So what was that story? In part, it’s a tale of savvy marketing.

With more than 100,000 passes to sell each weekend (at a minimum of $429 each), Coachella’s powerful Los Angeles-based promoter, Goldenvoice, is responding to shifts in popular taste — booking talent that is sure to attract the gigantic crowds no longer guaranteed by the likes of Arcade Fire.

And yet you could also sense something deeper in the attempt to broaden the diversity of the festival’s lineup. Coachella wants to matter; it wants to be seen as part of the solution to a lack of representation in culture — and also perhaps to chip away ever so slightly at its image as an escapist playground.

Indeed, the most striking performances felt in tune, not out of touch, with the complicated spirit of the day, be it the furious rhymes Staples spat while backed by a video screen showing brutal scenes of police violence or Beyoncé’s invocation in her song “Freedom” of images of chains and borders.

That’s not to suggest that the weekend had an explicitly political bent; I heard no mentions from any Coachella stage, for instance, of President Trump’s decision to bomb Syria on Friday night.

But with its clever and heartfelt use of so many proud HBCU traditions, Beyoncé’s knockout performance — which also included cameos by her husband, Jay-Z, and her sister, Solange, as well as a brief reunion of her old girl group, Destiny’s Child — was a vivid assertion of black self-determination at a moment when many are being forced to defend that concept.

SZA similarly pushed back against reductive ideas about African American womanhood in another very strong set that was as tender as it was profane. The Weeknd also skillfully disrupted his caricature as a suave but unfeeling brute; his headlining performance Friday, in which he sang as well as he ever has, offered a surprisingly subtle portrait of masculinity in crisis.

Coachella had more Latin acts than usual, such as adventurous Colombian American singer Kali Uchis and Mexico’s Los Ángeles Azules, which wasn’t just the first act up on the main stage this year but the first cumbia group to appear at the festival in its nearly two-decade history — an overdue correction for any event seeking to reflect the musical landscape of Southern California.

The concert also showcased Coachella’s highest-profile disco veteran yet in Nile Rodgers, who brought the latest version of his remarkably durable Chic to Coachella for a set that played like a funky history lesson as he ran through some of the many, many hits he’s written or produced, including Chic’s “Good Times” and “I’m Coming Out” by Diana Ross.

At one point, Rodgers described his enthusiasm for playing music as the thing that enabled him to beat cancer in recent years, and his comment made you think about how we often underestimate the rebellious potential of joy.

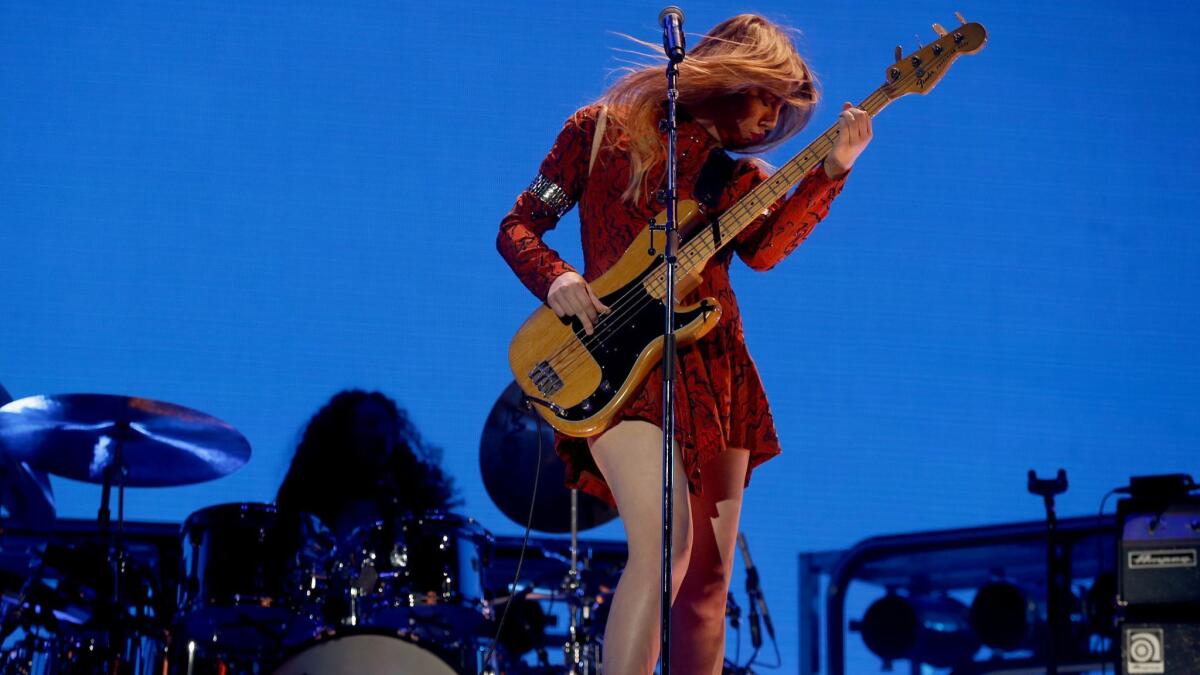

Like Coachella, disco was often seen as a form of escape. But Chic’s performance had less to do with escapism than with optimism; ditto an infectious set by the L.A. sister act Haim, which was the only guitar band I saw that put across even a fraction of Beyoncé’s exuberance.

Is looking on the bright side easier for successful pop stars than for average folks who can’t afford the hundreds of dollars to get into the Empire Polo Club?

Duh.

If Coachella took strides this year toward a more equitable — and lifelike — representation of different genders and races and cultures, the festival can still feel pretty discouraging on matters of class.

As the show has grown over the years, its VIP offerings have seemed to take up more and more of the psychic space at Coachella, which means that everywhere you look, you’re seeing someone who isn’t wearing the right wristband to get where he or she wants to go.

A festival isn’t a commune, of course; Goldenvoice isn’t required to feed everyone at one of its high-end, reservation-only dining spots.

But the constant reinforcement of how much you have (or how much you don’t) is an undeniable bummer when so much else about the experience is pointing you toward ideas of inclusion and affirmation.

Maybe next year some performer can blow away what remains of Coachella’s air of superiority.

As Beyoncé made clear, change is always within reach.

Twitter: @mikaelwood

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.