The four-decade odyssey of Chuck Berry’s swan-song album, ‘Chuck’

It wasn’t supposed to take four decades to make what turned out to be Chuck Berry’s final album.

In fact, very soon after the release of his 1979 work “Rock It,” one of the primary architects of the entire genre of rock ’n’ roll music started working on a follow-up at his home studio in his native St. Louis.

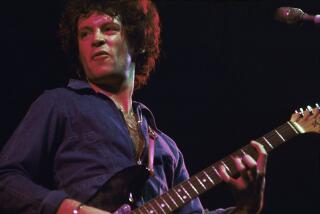

Rock ’n’ roll’s first guitar hero and its original lyric poet, Berry chipped away for nearly a decade writing songs. He demoed much of the arrangements himself, playing not only guitar and singing the lead vocals but providing piano, bass and drum parts in an effort to create a template for his band.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

“Then the unthinkable happened,” Berry’s son, Charles Berry Jr., told The Times earlier this week. “His studio burned down. It destroyed all the two-inch, 24-track tapes, all his recording equipment — nothing was left but cinders and scorched pieces of metal.”

That 1989 studio fire sent Berry back to Square One, and after spending two years rebuilding the studio, Berry senior started in again from scratch, slowly but surely trying to re-create what had been destroyed.

When he sat down backstage before a 2002 performance at the Universal Amphitheatre in Universal City, he told The Times that he was still working steadily and that the world would see another new Chuck Berry album one day.

“Now I’m writing about the life I’m living, and the life my generation is living,” he said at that time. “The generation right behind me is close to [that life], so they can look forward to it.”

This week the world at long last can hear the fruit of that long-maturing work in “Chuck,” an album that was completed last fall but wasn’t quite ready for release before Berry died on March 18 at 90.

“This was his next chapter,” said Charles Jr., who plays on the album along with his elder sister, Ingrid Berry, and his own son, Charles Berry III, Chuck’s grandson. “He worked very, very, very long and hard to get it released. He passed four or five days before ‘Big Boys’ was scheduled to be presented to the world.”

The song premiered as the album’s first single in March.

“That left us flat-footed,” he said. “This wasn’t supposed to happen. He’s supposed to be here. Of course he would have wanted it to be successful, but he didn’t need to do another album. His legacy is already secure. But obviously he still had something to say and he wanted people to hear it.”

The four decades that went into “Chuck” result in an eminently worthy final statement from the artist of whom Leonard Cohen once said, “All of us are footnotes to the words of Chuck Berry” and Bob Dylan lauded as “the Shakespeare of rock ’n’ roll.”

Shortly after Berry’s death, Rolling Stones guitarist and songwriter Keith Richards was asked whether it was Berry’s perfectly articulated vocals, his distinctive guitar work, his literate songwriting or his animated performance style that first captured his attention.

“Yes, yes, yes and yes,” he told The Times with a laugh. “I guess it was the combination of all of those things. To me, [Berry’s records] had sort of a crystal clear clarity of what I wanted to hear, and what I was aiming for.

“In retrospect, it was Chess Records,” he added, referencing the Chicago label that launched the careers of Berry, Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, Etta James, Bo Diddley and more.

“It was an amazing collection of musicians. And they were having fun — that was the underlying aspect of it all. There was an exuberance and they were not too serious. What was serious was what was going down — [but] they weren’t serious about it.”

The new “Chuck” album opens with “Wonderful Woman,” in what sounds like a happy reflection on the day he and his wife of more than six decades, Themetta Berry, met: “Well I was standing there trembling like a leaf on a willow tree/ Hoping them great big beautiful eyes would fall on me.”

“Big Boys” is a classic-sounding Berry rocker about a kid who yearns to up his game and fall in with the hip crowd. That song will be performed Monday, on “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon” by the one of the album’s guest artists, singer Nathaniel Rateliff, who will be joined by Fallon’s house band, the Roots. Charles Jr. and Charles III also will be there to help out, replicating their father’s guitar part from the recording.

“It kind of came out of the blue last fall,” Rateliff said in a separate interview of participating on the album. “It’s an honor and a privilege to collaborate with the guy who invented rock ’n’ roll, essentially. It’s funny the way Chuck uses words; John Prine does the same thing — he says things in a simple way that connects with everyone.

“Oddly enough,” Rateliff added, “my parents and other family grew up in Wentzville, Mo., [where Berry lived] and they used to hang out and party with a lot of those folks. It’s strange the way things work out.”

Among the songs on the album that Berry didn’t write is one from the Great American Songbook, which greatly influenced him as a young music hound who lived through the Depression and World War II.

J. Fred Coots and Haven Gillespie’s “You Go to My Head” allows Berry to channel his inner crooner and exhibit some of the impact such pre-rock singers as Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby had on him.

Ingrid Berry joins her father, singing and playing harmonica, on the poignant “Darlin’,” an aging parent’s twilight love letter to his child: “Lay your head upon my shoulder, my dear/ The time is passing fast away.”

“I’m going to brag about my big sis,” Charles Jr. said. “My sis was incredible on that one. I thought she was going to cry while she was singing it. Yes, I’m biased, but she’s fantastic. I’ll put her up against any of them, vocally or on harmonica.”

Fifteen years ago Berry spoke to The Times about one of the newer songs he was working on, quoting a metaphorically rich couplet: “A builder built a temple/ He wrought it with grace and skill.”

“Now that has nothing to do with ‘Come back, baby!’” he said with a little smile, indicating he’d moved well beyond the youthful exuberance, lusty romanticism and whimsicality that often surfaced in hits such as “School Days,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” “Roll Over Beethoven” and “You Never Can Tell.”

The lyric he quoted in 2002 has evolved slightly in the album’s deeply philosophical closing track, “Eyes of a Man,” in which he virtually writes his own epitaph as the referenced temple appears to represent his life’s work: “When other men observe its beauty/ They stand and see and sigh and sing/ Great is your work, oh yes, old builder/ Your fame shall never fade away.”

As Charles Jr. sees it, that sentiment has been borne out in the continuing life span of Berry’s music.

“He was in the game for 60 years, he toured for 60 years,” Charles Jr. said. “Did he ever think his legacy was going to fade? I don’t think so. Neither do I.

“Almost 40 years ago, NASA put ‘Johnny B. Goode’ on that record they sent out into space on Voyager. It’s something like 5 or 6 billion miles out there now,” he said.

In fact, the Voyager 1 probe is more than 11 billion miles out in space. “His music has already transcended the barrier of fad, and has taken its place in historical posterity,” said Charles Jr.

Follow @RandyLewis2 on Twitter.com

For Classic Rock coverage, join us on Facebook

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.