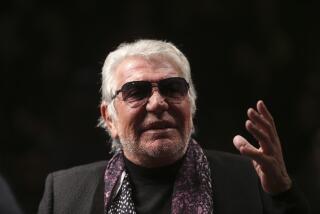

Carl Djerassi dies at 91; was instrumental in development of the Pill

Carl Djerassi was 28 and working for a small chemical company in Mexico City in 1951 when he helped make a discovery that changed the world.

His team created norethindrone, a synthetic hormone that became a key ingredient in oral contraceptives popularly known as the Pill.

It was, he wrote in a 1998 Los Angeles Times commentary, “a solution to birth control that has affected the lives of women (and hence men) in ways that few other postwar scientific discoveries have done.”

Djerassi, 91, who was called “The Father of the Pill” though he pointed out that many others were involved, died Friday at his home in San Francisco.

The cause was complications from liver and bone cancer, said his son, Dale.

The Austrian-born Djerassi, who became wealthy from the shares he bought in the chemical company, had several residences, including a penthouse in San Francisco. He was a professor of chemistry at Stanford University for more than 40 years and published more than 1,200 scientific papers.

But he was also, as he was proud to say, an “intellectual polygamist” deeply involved in the arts.

Djerassi wrote several science-themed novels, which he described as “science-in-fiction,” in addition to plays and three autobiographies. Although none of them became big hits, they drew praise. Novelist Iris Murdoch called his 1989 novel “Cantor’s Dilemma” “a brilliant tale of the morals and politics of contemporary science.”

He was also a noted art collector best known for his collection of Paul Klee works, and he founded an artists colony on a former cattle ranch in Northern California where artists, composers and writers could apply for work residencies.

And he got just enough involved in politics — supporting George McGovern for president in 1972 — to earn a place on the Nixon administration’s enemies list.

But Djerassi knew he would always be best known for his work as a young scientist.

“Any conversation,” he said in a Guardian interview last year, “begins with the Pill.”

Djerassi was born Oct. 29, 1923, in Vienna. His father, who was a physician, and his mother, who was a dentist, divorced when he was 6. He and his mother left the country in 1938 to get away from the Nazis’ oppression of Jews, moving first to Bulgaria and the next year to New York, where they arrived with almost no money.

Djerassi won a scholarship to Tarkio College in Missouri, later studying chemistry at Kenyon College in Ohio, where he graduated summa cum laude before his 19th birthday, according to a Stanford biography. He earned his doctorate from the University of Wisconsin in 1945.

His first involvement in a scientific breakthrough came while he was in graduate school — he shared in the development of an antihistamine that became widely used. “To see the very first thing I worked on not only work, but, gee whiz, hundreds of thousands of people actually took it, well, that was just great,” he told The Times in 1998.

After earning his doctorate, he took a job as a research chemist in New Jersey, moving to Mexico City in 1948 to become associate director of chemical research at Syntex, a company working to synthesize hormones. He worked with researchers George Rosenkranz and then-student Luis Miramontes, who on Oct. 15, 1951, took the final step in creating norethindrone. The three men shared in the patent.

The Food and Drug Administration approved norethindrone for contraceptive use in 1962, and by 1964 it had the major share of the U.S. market in birth control pills, according to an account by Rosenkranz.

A year after the creation of norethindrone, Djerassi left the company to teach at Wayne State University in Detroit; he went to Stanford in 1959. He concurrently held positions at Syntex from 1957 to 1972, during which time it moved to Silicon Valley and became a major force in the field. It was acquired by Roche Holdings in a $5.3-billion deal in 1994.

Djerassi also helped found Zoecon, a company that developed methods for insect control.

The Pill has met with controversy over the years, including arguments from feminists that it made contraception primarily a female chore. Djerassi sympathized, telling the Guardian in 2010 that a primary disadvantage of the Pill is that “men won’t take responsibility ... they shrugged and said: ‘All women are now on the Pill, I don’t need to bother.’ This has become another women’s burden.”

But he said he doubted that any pharmaceutical company would develop a male oral contraceptive, partly because men would hesitate to take it. “The first question a man would ask is: ‘Would it affect my potency?’”

The major tragedy in his life came in 1978 when his artist daughter, Pamela, committed suicide after struggling with depression. The artists colony on his ranch land was founded in her honor.

Djerassi started writing a novel in the 1980s in the wake of a breakup with acclaimed biographer and teacher Diane Middlebrook. After they reconciled and married in 1985, he had a bout with cancer. “I decided that if I lived, I would like to live another intellectual life,” he told The Times in 2004. He had no plans to retire from his new life as a writer.

“I look ahead because I know time is running out,” he said in a 1998 Times interview. “I am not going to live forever. But I always think something wonderful will be around the corner.”

In addition to his son, Djerassi is survived by stepdaughter Leah Middlebrook and a grandson. Diane Middlebrook died in 2007. His two previous marriages ended in divorce.

Twitter: @davidcolker

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.