Great Read: Physicists, others using science to help art of film animation

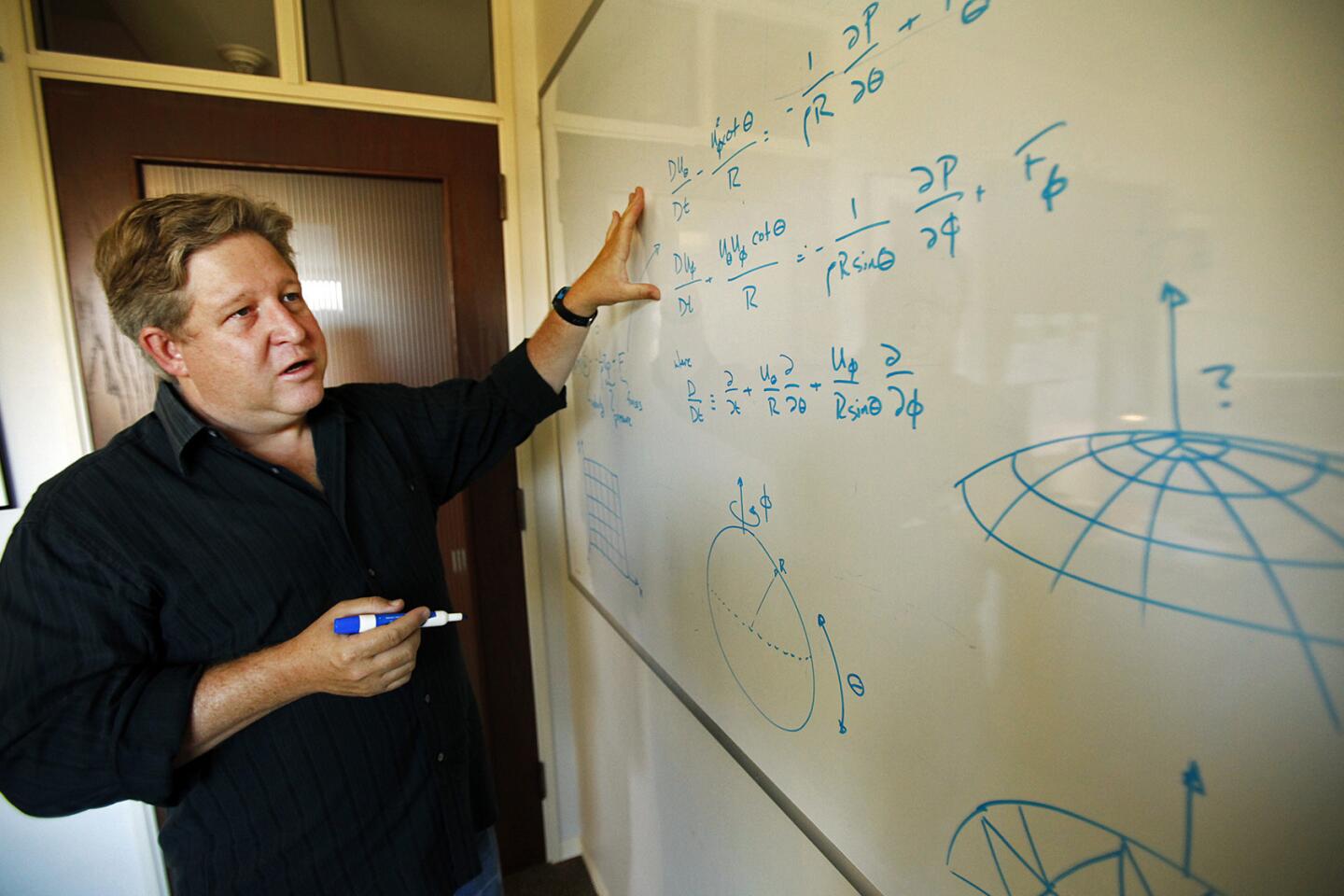

In a small, utilitarian office in Glendale, Ron Henderson methodically jotted down equations for Isaac Newton’s Three Laws of Motion on a whiteboard next to his desk.

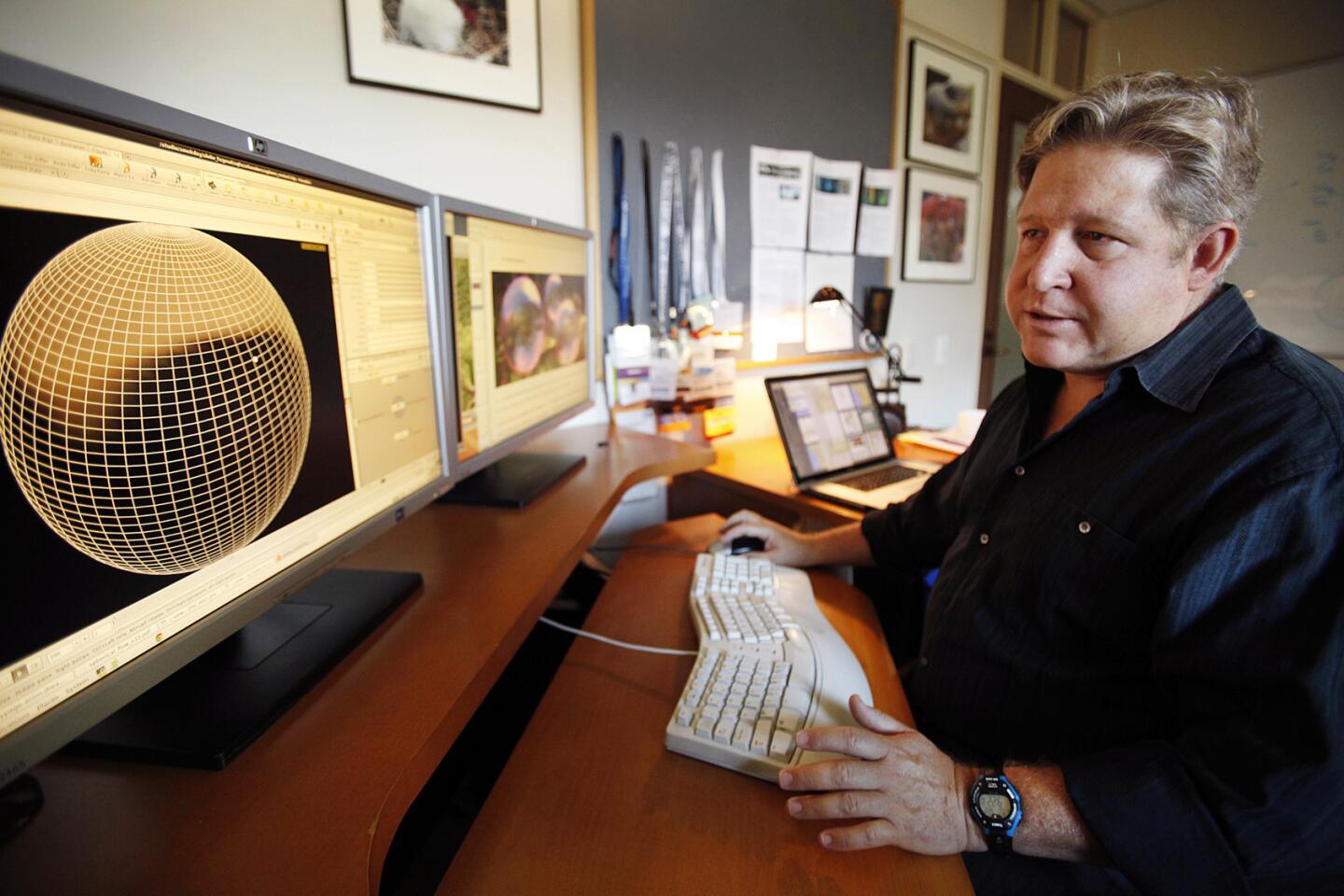

The equations, the physicist explained, are the mathematical building blocks for constructing a three-dimensional, bubble-like sphere.

Henderson could easily have been preparing a lesson at Caltech, where he once was a faculty member. Instead, he was at DreamWorks Animation’s Tuscany-style campus, doing his part to bridge the divide between art and science.

Henderson was explaining the math behind a fluid-simulation technology that would help artists working on the upcoming movie “Home” draw soap bubbles inhabited by a race of diminutive aliens called the Boov.

To give them visual references, Henderson and his team began by studying drawings and photos of soap films and bubbles last year. He invited a physicist colleague from San Jose State to give a lecture titled “Bubble Science.”

The physicist, Alejandro Garcia, took a low-tech approach. He arrived at the studio with boxes of liquid soap and party bubbles, using a plastic wand to fashion large bubbles for an audience of artists and technicians gathered at an outdoor amphitheater.

“He did cool things that we’re not doing, like what happens when you make a soap bubble out of hydrogen and set it on fire?” Henderson said, chuckling. “What does that look like?” (The bubble made a loud boom and burst into a fireball when an assistant took a Tiki torch to it.)

That’s the kind of thing that happens when the scientific set makes the move to the movies.

“What we’re doing here is creating tools for artists,” Henderson said. “I think it’s going to be a success.”

::

Henderson, 47, is part of an expanding cadre of high-level physicists, engineers and other scientists, including many former NASA employees, who have left careers in aerospace and academia to work in the movie business.

Demand for their services has grown as animated movies, once created by hand, push the boundaries of what can be created on a computer screen. Artists at DreamWorks, Disney-owned Pixar and other studios increasingly rely on the services of people such as Henderson to create complex algorithms to simulate realistic-looking water, fire, dust and other elements in movies packed with action and special effects.

“The physics behind what’s happening in these movies is incredibly complicated,” said Paul Debevec, a computer scientist and chief visual officer at the USC Institute for Creative Technologies. “You need real scientists to understand what’s going on. These are Ph.D.-level folks who could have been publishing papers in Physics Today. Instead, they are working on Hollywood blockbuster films.”

Scientists who leave academia for Hollywood risk losing some prestige among their peers. “My advisor at Caltech got some flak from Princeton, saying ‘How come you guys let him leave?’” Henderson said.

Although they typically get paid more in the film business, Henderson says money isn’t the main draw. He cites the excitement of working on movies and the challenge of finding solutions to technical problems.

DreamWorks has one of the largest contingents of scientists.

“We have sculptors and painters working side by side with software developers and particle physicists,” said Dan Satterthwaite, the studio’s human resources director.

The company’s research and development group has about 120 members with master’s and doctoral degrees in such fields as cognitive science, astrophysics, aeronautical engineering, chemistry, mathematics and computer science. Nearly a dozen of them are former employees of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The studio has even hired biologists to advise animators on how to correctly illustrate the proper branch structure on a tree.

“This whole company is a very interesting mix of left brain and right brain,” said Jim Mainard, head of digital strategy and new business development for DreamWorks. “Often we end up at the same place, but from different directions.”

Mainard, himself a computer scientist, used to work for a NASA contractor involved in the Hubble Space Telescope. He also created film simulations for the Navy before DreamWorks hired him to help the studio build its own pipeline of computer-animated movies.

“When I came out of college, I never thought I would work in the entertainment business,” Mainard said. “For me, it was just a great time to make the transition. We were having our first child and I just liked the idea of making animated films. I thought that would align with having a family.... Making people laugh is a great legacy.”

::

Henderson’s office is cluttered with hints of his academic past. A bookshelf is lined with scientific texts with titles such as “Fluid Dynamics” and “Differential Equations.” On his desk is a manuscript for a book he co-wrote called “Multithreading for Visual Effects.”

Pinned on the front door is a congratulatory letter for a Technical Achievement Award he received in February from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Henderson, a director of the DreamWorks research and development team, received the award for developing a fluid-simulation system called Flux, which creates high-resolution effects 100 times faster than in the past.

“I was at home in Kentucky for the holidays when the announcement came out at midnight,” Henderson said. “I woke up my wife and kids.... It was a big honor.”

Henderson was born and raised in a small town near Nashville. A math whiz in high school, he dreamed of becoming a rocket scientist, studying aeronautical engineering at Purdue University. Later, he received a doctorate from Princeton in mechanical and aerospace engineering.

His groundbreaking research in the field of fluid dynamics landed him a job as a faculty member at Caltech, where he taught for five years before taking a leave to work for a commercial software company, ArsDigita.

When that company was sold in 2002, Henderson decided to make a permanent switch to the private sector. He joined DreamWorks, where a former Caltech colleague had worked.

“Science can be a very lonely activity,” he said. “I wanted to use my background in computational physics, but I wanted to have the experience of working with people and being able to see the results of what I did.”

Seeing “Shrek” also piqued his scientific curiosity about the new medium of computer-generated imagery, or CGI, that was changing how movies were made.

“What astonished me was how much detail and motion there was in every frame, the motion of the trees, the grass and all the other elements,” he said. “It intrigued me to the point that I didn’t think it was possible.”

::

Part of Henderson’s role is to foster a culture of collaboration between workers from disparate backgrounds. Artists and engineers hold biweekly meetings and also work on the same floor to interact more easily.

Much of their focus is on what he calls improving the “scale of production.” Because there are so many shots in a single movie — one film might have 700 scenes with fire, for example — Henderson and his team spend much of their time trying to devise more efficient ways of simulating effects through improved software and hardware.

Then there are specific technical challenges of creating something visually unique to the look of each film, such as the frost in “Rise of the Guardians,” the stylized cannon fire in “Kung Fu Panda 2,” or the ice-breathing dragon in “How to Train Your Dragon 2.”

His latest challenge was creating the bubble-like spheres in “Home,” which would provide the unique look to spaceships in the movie.

Turns out, creating a computer animation image of a bubble on a flat surface is one thing, but wrapping that image around a floating soccer-ball-like sphere is a much trickier problem of math and physics.

Using a variation on a numerical weather-prediction model, Henderson tapped into his knowledge of fluid dynamics to devise a new way to simulate flow on a sphere.

The fact that few moviegoers will appreciate the technical achievement doesn’t bother him.

“I can go work for an oil company or I could go back to academia,” he said, “but the personal gratification of doing something where you can clearly see the results of your work, and where you feel you are providing a unique benefit to the artists — that’s what keeps me coming here every day.”

Twitter: @rverrier

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.