LAPD officer in ’81 killing had front-row seat on Ferguson controversy

In 1981, David Klinger, a white LAPD officer, shot and killed a black suspect in South Los Angeles. Today, Klinger is a professor of criminal justice in St. Louis, where he’s had a front-row seat on the raging controversy over the shooting death of a black man by a white officer in Ferguson, Mo.

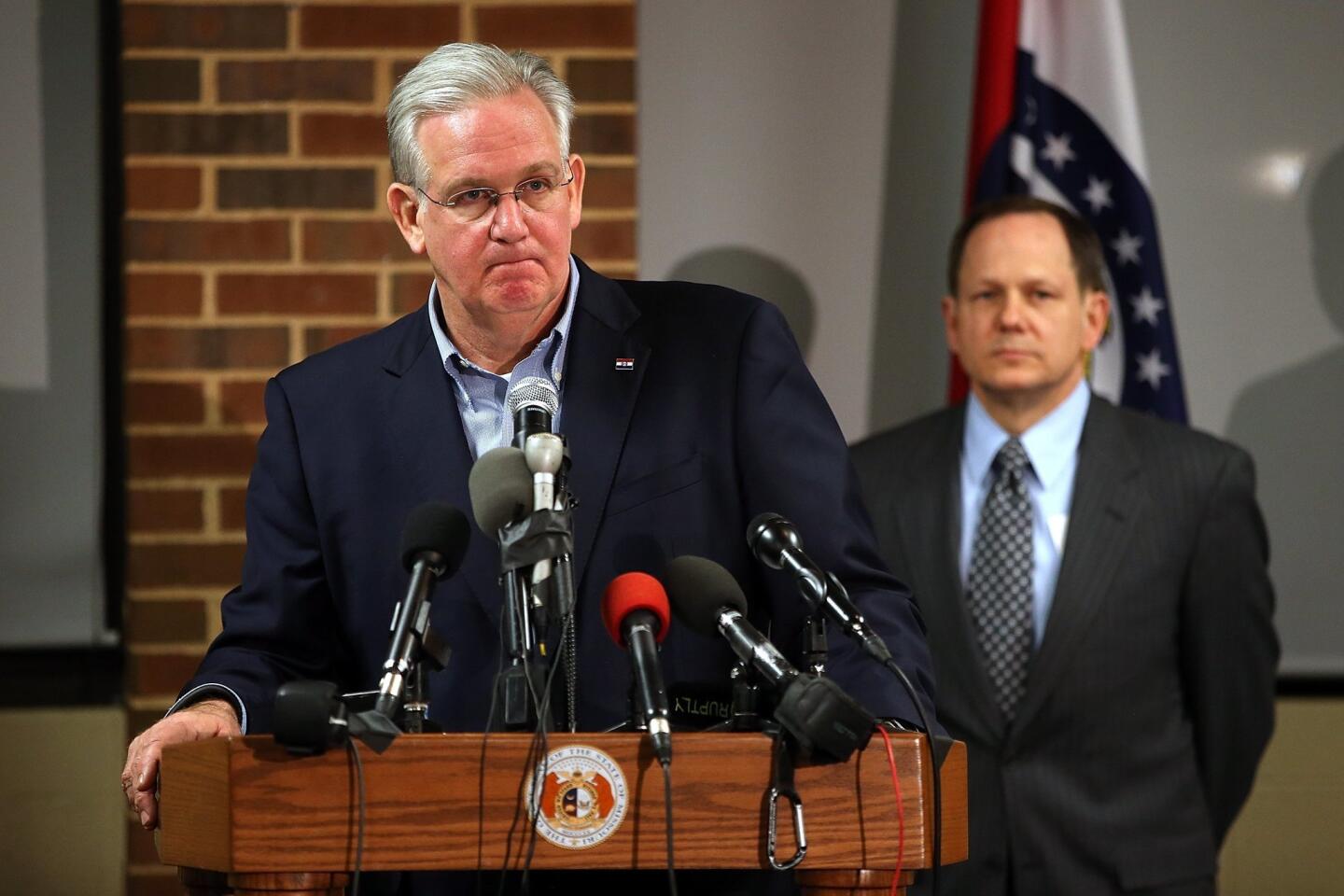

Those things made me think that he might have something interesting to say about the shooting of Michael Brown by Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson, and he did. But when I reached him Tuesday, he made it clear that he wouldn’t speculate about whether the grand jury made the right decision Monday not to charge the officer with a crime.

“I wasn’t there, and neither were any of these critics,” Klinger said.

I wasn’t there, either, though I do have some questions about whether Wilson could have called for backup or tried to use a nonlethal weapon, given the fact that Brown was unarmed. And I have to wonder about the motive for secret grand jury proceedings rather than an open judicial process.

But at the center of this case — along with issues of race and police-community relations — is the question of when police should be allowed to use deadly force. Are those policies clear enough to police? And do they get adequate training in how to de-escalate conflicts?

Sometimes it’s crystal clear when to use deadly force, Klinger said, and sometimes ambiguities cloud the decision. He speaks from authority: Not only has he investigated the topic extensively as a professor and researcher at the Police Foundation, but he also interviewed dozens of officers involved in fatal shootings for his book, “Into the Kill Zone: A Cop’s Eye View of Deadly Force.”

That book begins with an account of what happened in Klinger’s case in South Los Angeles in 1981, when he was a rookie assigned to the 77th Street Station. He had been pulled out of the Police Academy four months earlier, two months short of the full term, because of stepped-up deployment after the late 1980 shotgun killings of four people at a Bob’s Big Boy on La Cienega Boulevard.

Klinger had become an officer with the goal of stopping the tide of gang violence, and he and his partner, Dennis Azevedo, were responding to a call reporting a barricaded gunman on the north side of Vernon Street.

“There were a number of people on the south side of the street and we told them to get out of there,” Klinger said. “They all left but one guy, and when Dennis went to get the guy out, he attacked.”

Klinger saw the attacker stab his partner once in the chest with a butcher knife and ran toward the two men as they wrestled on the ground. Klinger had just been trained on deadly force a few months earlier, with classroom lectures and mock scenarios that required split-second decisions. He had been told to do everything possible to avoid shooting, and one instructor said he would never be criticized for not shooting.

So he began trying to wrestle the knife away.

“I put both my hands on the guy’s wrist,” Klinger said. But the man was powerful, and managed to raise the knife with both hands as if prepared to plunge it through Azevedo’s throat.

“Dennis screamed, ‘Shoot him,’ ” said Klinger, who took aim and pulled the trigger from two feet away, firing a bullet into the attacker’s chest.

“It went underneath his armpit, tunneled through his left lung, hit his aorta, went into his right lung and lodged under the skin on the right side of his body,” Klinger said.

In retrospect, Klinger said, he believes he risked his own life and that of his partner by trying to wrestle the knife away rather than shooting the attacker. Still, the killing took an emotional toll for years, even though he believed he did the only thing he could have done. Eventually, rather than remembering the shooting as the night he took someone’s life, he began thinking of it as the night he saved someone’s life — his partner’s.

Klinger doesn’t suggest that his own experience helps clarify what happened in Ferguson. He did say, however, that no officer can get too much training on deadly force, and it should be repeated annually, precisely because deadly force situations are rare.

“Unfortunately, there are academies around the country that have less than stellar training on use of deadly force,” Klinger said.

It’s hard to imagine why that is, given that the safety of officers and the public is at stake. It’s also hard to believe, as Klinger noted, that there’s no national database of officer-involved shootings. The ages and races of officers and victims, as well as data on mentally ill victims, should be routinely analyzed in the interest of clarifying the record and informing policymakers.

Klinger said he doesn’t have evidence that improving police-community relations leads to fewer uses of deadly force, but the merits of better interactions are obvious. In the immediate aftermath of the shooting of Michael Brown, Klinger was shocked not to see high-ranking police officials meeting with clergy and other civic leaders, and he wondered if they had built those vital relationships.

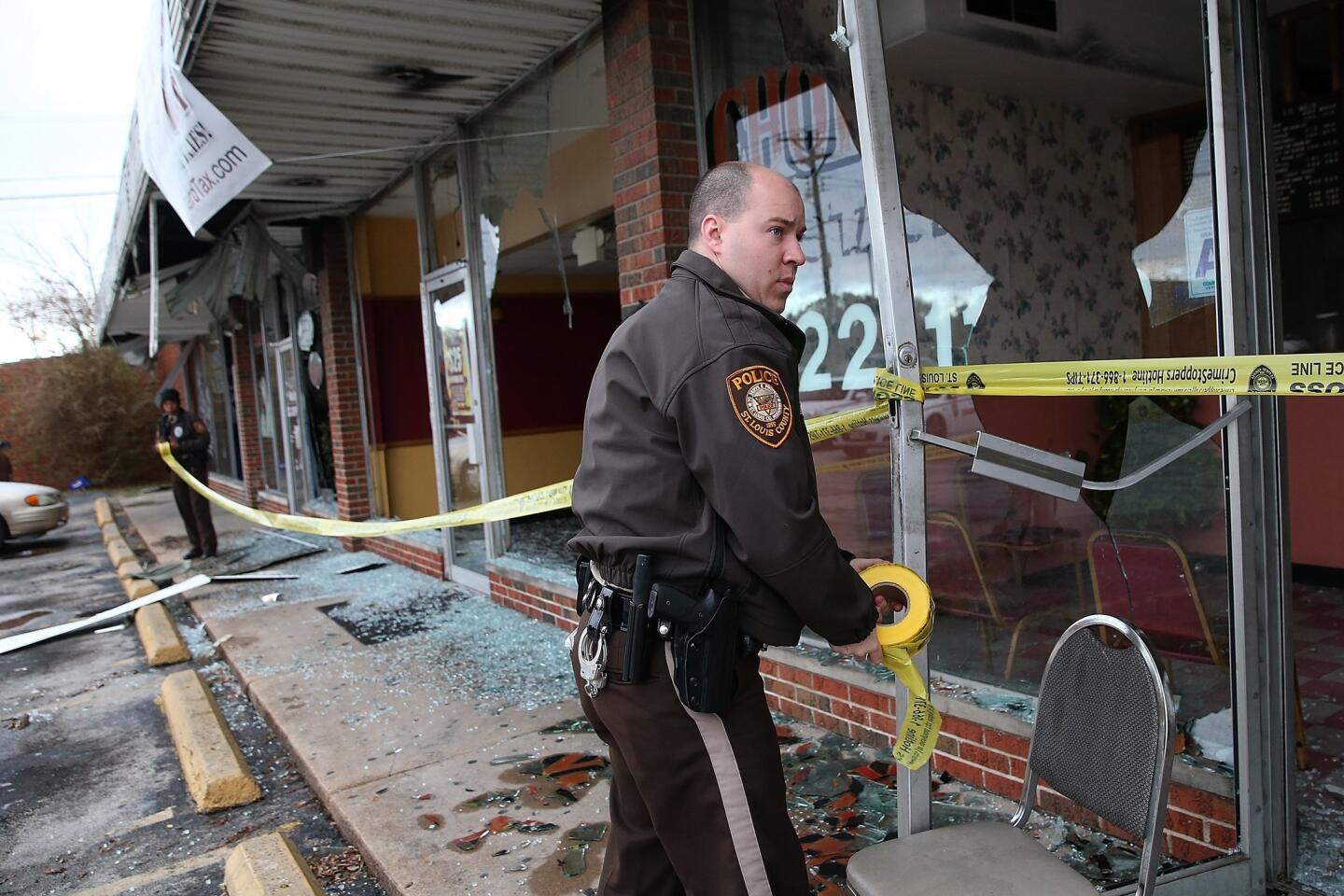

He was also shocked to see the way canine units were deployed by police during the subsequent unrest.

“I was thinking, ‘Does anybody know about 1956 in Birmingham, Montgomery and Selma?’ I was waiting for the fire hoses to show up. It’s a shame to be ignorant about history. You’ve got an agitated community, and you’re going to put canine officers on the front line? To me there’s obviously some kind of breakdown there.”

If nothing else, the story at his doorstep in Missouri has given Klinger plenty of material. Justice in a deadly force case is a process, he tells his students. Do a thorough investigation, vet all evidence, be faithful to due process and no matter how high passions are running, “don’t rush to judgment.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.