Aaron’s Law: What’s in a name?

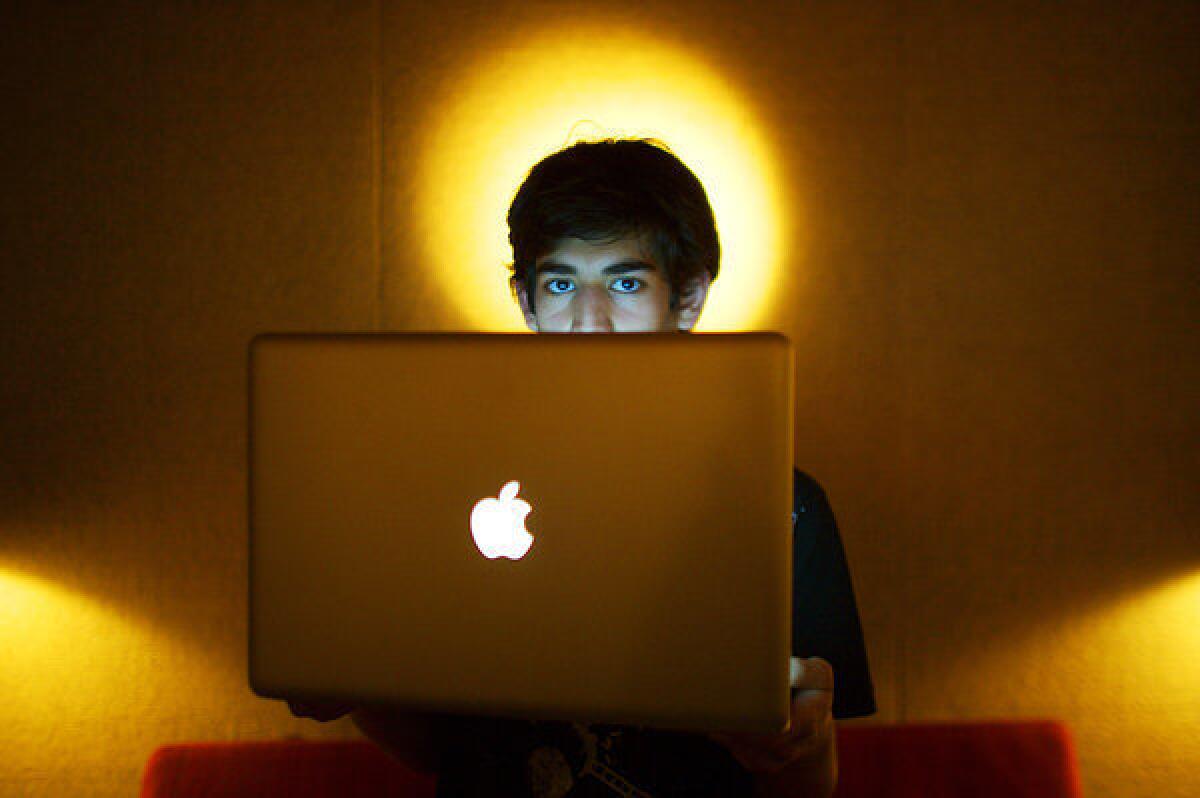

The Times has an editorial Friday about legislation proposed in the aftermath of the suicide of Aaron Swartz, the computer prodigy who was being prosecuted by the federal government for allegedly gaining unauthorized access to an online repository of academic research. Known as Aaron’s Law, the bill by Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-San Jose) would bar computer or wire fraud prosecutions based on violations of a website’s terms or policies if such violations were the “sole basis” for determining that access was unauthorized.

As the editorial noted, Aaron’s Law might not have protected Aaron Swartz, who was accused of doing more than just downloading more articles than permitted under the terms of service. But put that issue aside. Calling the bill Aaron’s Law perpetuates a practice I long have found problematic: treating the legislative process as a way to obtain justice (often posthumous justice) for an individual.

We’ve had Megan’s Law and Jessica’s Law (dealing with sex offenders and named for slain children); the Brady Bill, a gun-control measure named for Jim Brady, the press secretary wounded in the attempted assassination of President Reagan; and the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, named for victims of homophobic and racist attacks, respectively.

Although these laws were enacted in recent years, the practice of naming laws for victims goes back at least to the 1930s and passage of the so-called Lindbergh Law allowing for federal prosecutions of kidnappers who transport their captives across state lines. The law was named for Charles Lindbergh Jr., the famous aviator’s toddler son who was abducted and killed in the “Crime of the Century.”

I don’t object to any of these laws on the merits. Sometimes a poignant individual case calls attention to a systemic but long-ignored problem. At the same time, I worry that attaching the name of a sympathetic victim to a bill can stampede legislators into approving a measure to pay homage to an individual rather than because the law is needed. It’s harder to oppose Aaron’s Law than the Internet Terms of Service Amendments Act of 2013.

More cosmically, the practice of naming bills for individuals encourages the notion that the job of Congress or a state legislature is to avenge individual wrongs rather than establish broad policy. It’s an impression that politicians are only too eager to cultivate. Their names go on the bills too.

ALSO:

McManus: For Democrats, unity and its pitfalls

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.