Great Read: For former professional drummer Robin Russell, no gig tops Griffith Park

For 14 years now, sometimes three times a week, Robin Russell has gotten up around 3 a.m. and driven his maroon van from Pasadena to the same spot in Griffith Park, not far from the zoo. In the dark, he rakes out a small clearing under an oak tree, unpacks a six-piece drum kit and sets up, everything in its place on an old piece of red carpet.

And he plays. He plays if people are there to hear. He plays if the birds and coyotes are the only ones listening. Often he starts under the stars. He plays through sunrise and on into the afternoon. He leaves before dark, the time depending on the season.

“Drums were made to play outdoors. That’s what they were for in the beginning,” Russell says.

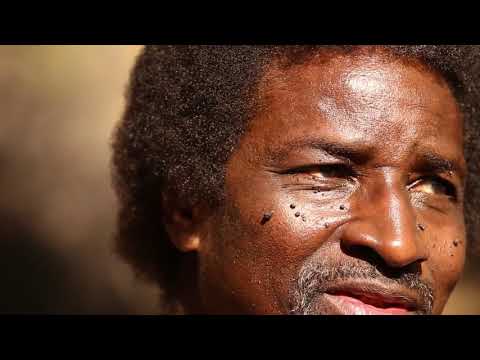

At 63, he’s got muscular arms and a sweet, open smile. His uniform is black pants and a black tank top; he wears two pendants, a peace sign and an ankh, the ancient Egyptian symbol for eternal life. There’s also an ankh dangling from his left ear. He keeps his phone in his sock.

Russell has played for crowds in London’s Wembley Stadium, on tour with Little Richard. He’s performed on “Soul Train” as the drummer for the popular 1970s soul-funk band the New Birth.

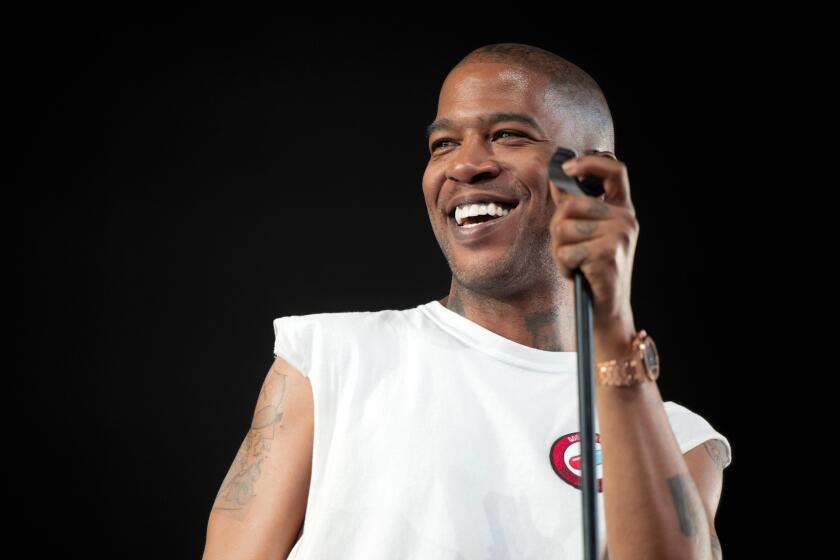

Drummer Robin Russell, who once played Wembley Stadium touring with Little Richard, keeps a steady beat outdoors at Griffith Park.

SIGN UP for the free Great Reads newsletter >>

It’s not applause he’s looking for in the park.

“He is at his highest delight when he is out there playing the drums,” says his wife of 30 years, Angela. “His connection with his drums is like a voice is to a singer. They are one.”

Plenty of other people play music in Griffith Park. There’s a Sunday drum circle, and guitar players show up all the time. But every week? For so many years?

And why, exactly?

“The environment here is perfect for creativity, just very inspiring,” Russell says. “Out here I feel connected with Mother Nature, with the universe, with the elements.”

Russell’s spot is officially known as NYC1, after a Great Society program called the Neighborhood Youth Corps. It’s at the edge of a small field, with three picnic tables at the side of the road. One warm morning, owls hooted as he wheeled his instruments from the van to his dirt circle stage under a full moon.

As he sets up, he puts on the Brazilian singer Bebel Gilberto, softly. He centers his bass drum in line with a tree, parallel to Griffith Park Drive.

“I like to be there in the darkness as long as possible,” he says. “It gets so bright out there. I don’t need a light.”

And he doesn’t need help setting up.

“It’s a little like a crossword puzzle. For the most part, it’s better if I do it myself,” he says.

He’s meticulous. Once the drums, the color of his van, are in place, he lays the dolly on its side and piles on his cases — stenciled with his name from his touring days. Three canvas director’s chairs are set out in front, one for him during breaks, one for a reporter and one just in case. He brings breakfast, lunch, ice and water, extra sticks and rain boots.

It’s beautiful that a musician uses music for his own well-being -- it keeps him calm, at peace. It’s a part of him. It wasn’t a gig, it wasn’t a job.

— Scott Galloway, longtime friend and music journalist

From a branch he hangs a homemade feeder into which he drops some bread pieces for the creatures. One last thing before the music starts: He carries a plastic bag and a rake on a walk around the grass to pick up trash.

“Sometimes I feel like I am the unofficial keeper of the grounds,” he jokes.

All of his substantial equanimity falls away when he picks up the sticks. For 45 minutes he plays nonstop, grimacing, humming under the beat. The music crashes, meanders, scampers, amuses, hypnotizes.

“Rob is a very strong, tight technical drummer,” says Vance “Maddog” Tenort, a trumpeter who first played with Russell when they were teenagers in groups like Little Rudy and the Shades of Jade. Scott Galloway, a longtime friend and music journalist, describes Russell’s drumming as “very, very funky. He has incredible dynamics.”

Russell started out as a sax player in junior high and then at Crenshaw High School. But as he began playing gigs, he didn’t like that the sax put him out front. One day he sat down at the drums, “and that was the moment,” he says.

He got a part-time job at a library for money to buy his own drums and started teaching himself to play. One night, he says, Little Richard came to a club where he was performing. Afterward, he asked Russell to join him on tour in Europe.

“My jaw was on the floor. I was a 19-year-old kid,” Russell says. That led to the R&B group the Nite-Liters and the New Birth.

These days, Russell plays freelance in clubs. And he plays along the route of the L.A. Marathon, including the year his wife ran. But most regularly, he plays in the park. He drums, takes a break, drums, reads the paper, drums, snacks. It’s an easy, peaceful rhythm.

“It’s just so magical,” Russell says.

He says he’d vowed to play in Griffith Park back in his sax days. He used go to there with his parents and became entranced by the hippies and the music he heard. So in the ‘70s, during his New Birth days, “I just felt that now is the time for me to take my drums to Griffith Park,” and he played near the Griffith Observatory. Later he and Tenort attracted a crowd playing near the merry-go-round. So began the habit of playing when he was in town.

“I was a lot younger then. I don’t think I even took breaks. I would only go to the restroom,” he recalls.

Life intervened for many years, but finally Russell was ready to make his outdoor music a real habit. “I just wanted to find a spot where I could woodshed, be in nature, play what I want.”

He drove around the park until he found the tree and knew the spot was for him.

Russell used to move his whole drum kit as the sun moved across the sky. Now he has a red umbrella that he shifts to make whatever shade the oak can’t provide. He doesn’t mind that, or the packing and unpacking over and over.

“The things I see and feel out here are an influence on what I play,” he says.

Sometimes people who like his music donate money or buy his CD. But he doesn’t put out a hat.

“The thing that’s really, really special about Robin is that he has a spiritual connection to this instrument. He’s a nature lover,” Galloway says. “It’s beautiful that a musician uses music for his own well-being — it keeps him calm, at peace. It’s a part of him. It wasn’t a gig, it wasn’t a job.”

Senior Ranger Albert Torres appreciates the drummer.

Russell takes a break during his day of drumming in Griffith Park.

“It’s such a draw to have a person in the same place for so many years,” he says. “It’s a real good aspect to the park.”

On weekends, there are people, parties. On a recent Saturday, a visitor from Sweden got his picture taken with Russell. A group of people making a documentary about civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer offered him lunch. He’s played for a game of musical chairs at a kid’s birthday party. Sometimes kids come by, and he’ll let them have a go.

“One time, I noticed one little boy. I thought he had his arms tucked into his shirt. But I said, ‘Wait a minute. He doesn’t have arms.’ He came by and asked if he could play. He sat on the stool and picked up the sticks and played with his feet. He is a real hero,” Russell says. “Nothing stopped him.”

Last year, Russell’s parents died, and two days after his mother was buried, Russell was playing in the park when a white dove dropped down. “In 13 years I never saw a white dove. It was a messenger, a symbol of the deceased,” he says.

Over the years Russell has come to know a great deal about his corner of Griffith Park.

He knows where all the sprinklers are, and he says the groundskeepers don’t turn on those that would spray him or his drums when he’s out there. On particularly hot days, he’ll pack swim trunks and take a break to run through the water.

He remembers when there were grills in the grass. And the 2007 fire in the park. “I was playing and I smelled smoke. I could see ashes coming down. There was a big orange and black cloud over the trees. The ranger came by and said, ‘You have to get out of here.’ I never packed up so fast.”

Russell’s place is marked, and not unlike the way the other inhabitants of nature mark their spots, it’s obvious if you know what to look for. Above him, in the tree, he’s tied three drumsticks. It’s his place.

MORE GREAT READS:

After 30 years of helping gang members, Father Greg Boyle is slowing but determined

A classic car mystery: Who owns the real ‘million-franc’ Delahaye?

Russia’s military clubs for teens: Proud patriotism or echoes of fascism?

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.