Review: At LACMA, a don’t-miss African art exhibition full of mystery and beauty

Object for object, “The Inner Eye: Vision and Transcendence in African Arts” provides perhaps the most flat-out beautiful museum exhibition in Los Angeles so far this year.

A selection of about 100 sculptures, many of them extraordinary, dates from the 13th to the early 20th century in a variety of cultures in West, Central and East Africa. Polly Nooter Roberts,

Frequently the eye becomes a kind of mysterious membrane between material and spiritual worlds.

Take a Liberian mask whose symmetrical face with protruding eyes and mouth is enlivened by dramatically asymmetrical décor. One eye is crossed out, canceling its outward view. A small length of twisted cord creates a puckish grin when attached over a row of jagged teeth. The mask gleefully seems to say, “I know something you don’t know.”

Esoteric knowledge is a prominent undercurrent throughout the show, nowhere more beautifully — or mysteriously — expressed than in a Lega mask from what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. A white oval head with a broad, heart-shaped face above a narrow, lozenge mouth is either without eyes or, possibly, is all eyes. Blindness reverberates with all-seeing insight.

The ceremonial mask, typically attached to the body as a talisman rather than worn over the face, is like an abstract echo of a human skull. It nods toward ancestors long gone but present during the ritual.

The LACMA show is divided into eight thematic sections. Sometimes the thread unravels and the show is hard to follow.

Among the more compelling groups is “Beholding Spirit,” which looks at the way royal trappings — a throne, a scepter — embody spiritual power that its user then wields. A commanding power figure (or nkisi nkondi), hammered with metal spikes across broad shoulders and atop sturdy columnar legs, is a “Vigilant Sentinel” looking skyward through shell-covered eyes: Earth meets sea meets sky in a mighty guardian. And a staring Dogon hermaphrodite, identifiable as such by conical breasts and a scruffy beard, is “Envisioning Origins” through the union of male and female.

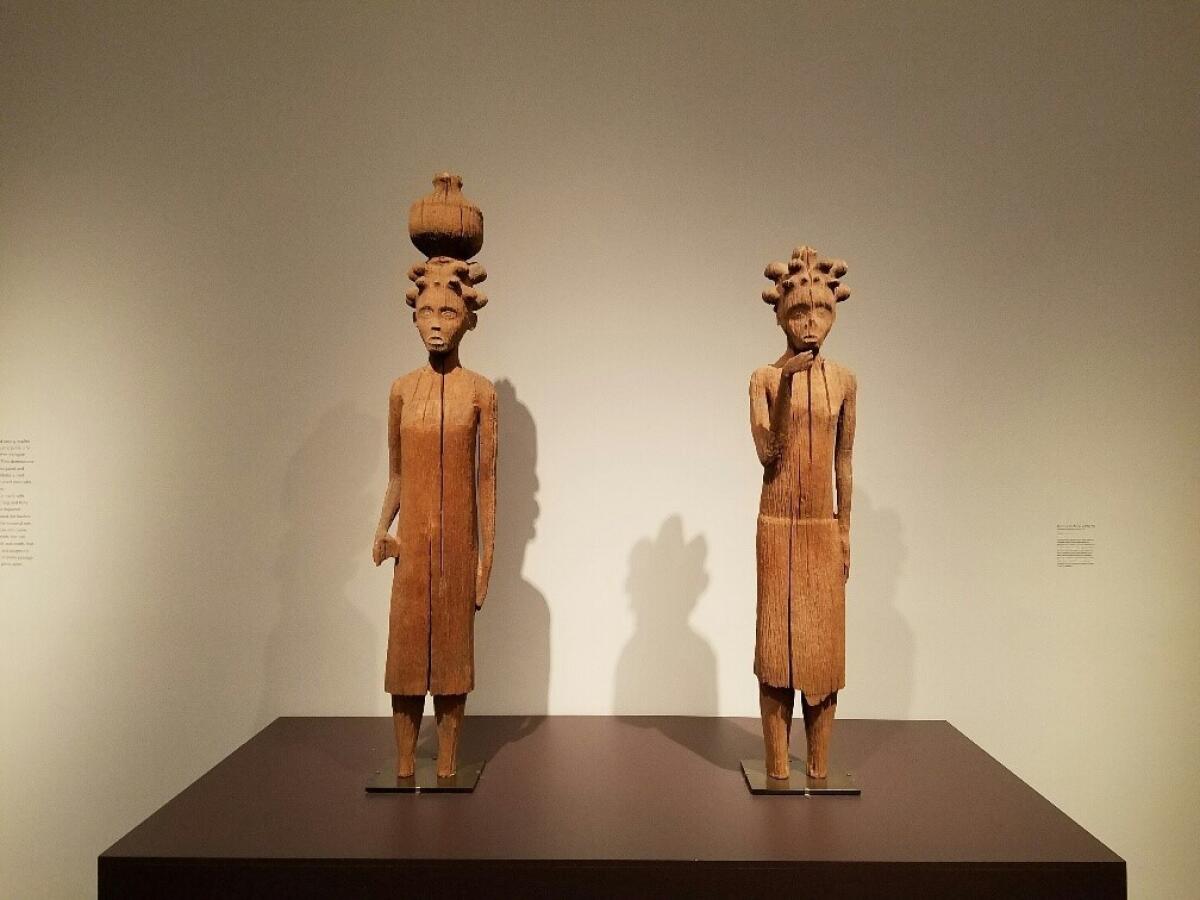

Some works are surprising in a singular way. Nearly life-size commemorative carvings of a male and female pair of tomb guardians from Madagascar look almost contemporary; weathering outdoors has softened features into smooth planes of unadorned wood. Gone are the rifle and lance he once held for protection, while the jug balanced atop her head speaks of nurturing sustenance.

On the other hand, the section devoted to the “Maternal Gaze” is fairly prosaic. Art representing the familiar subject of mother and child seems separate from a distinctive consideration of “the inner eye.”

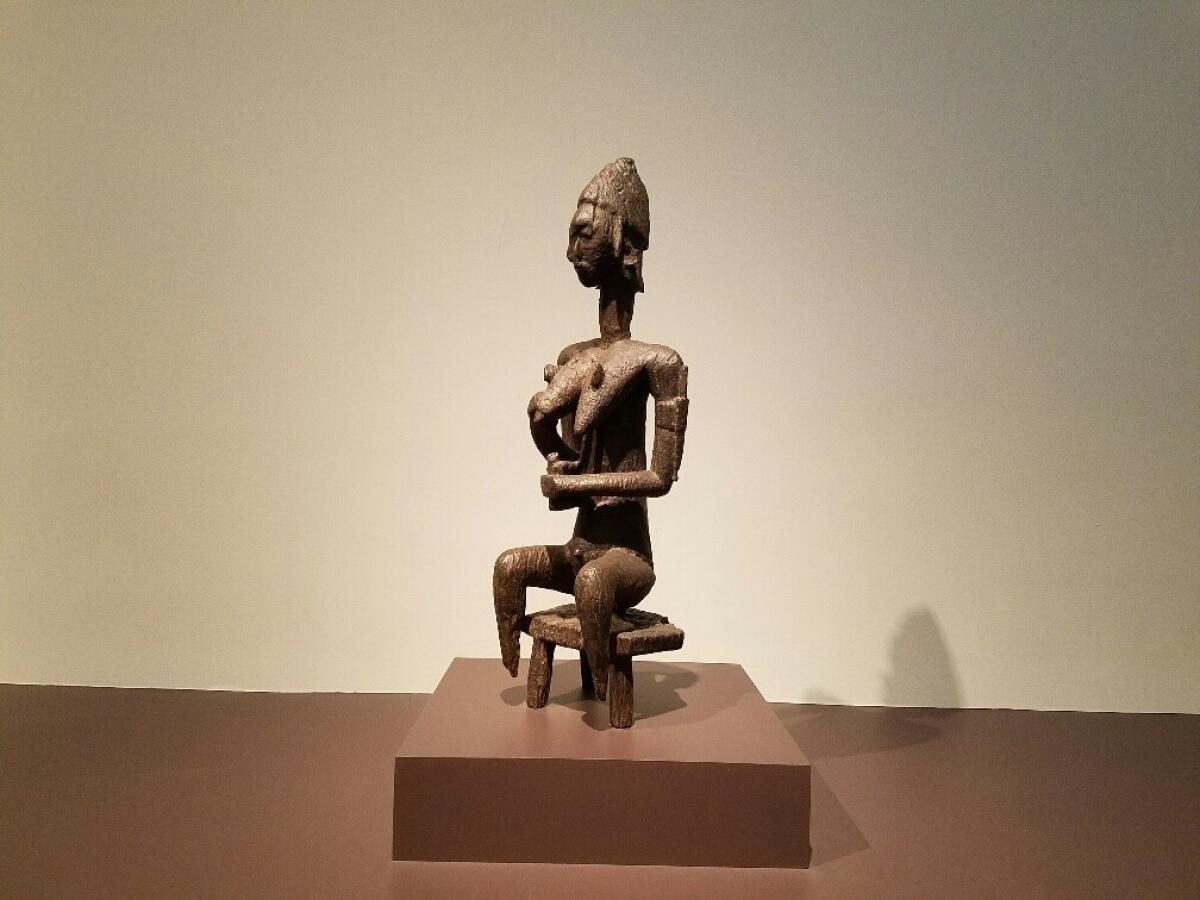

Yet the section does offer some context for a marvelous LACMA treasure acquired in 2014 — an extremely rare fertility figure carved by the Bamana peoples of Mali in the late 13th or 14th century. (Most wooden African sculpture dates from the 19th century and after, a testament to the fragility of the material in sub-Saharan climates.) Three feet tall, seated upright on a bench, limbs and torso stretched and straight as an arrow, she’s a tower of expansive strength, sheltering the remaining fragments of her offspring.

The sculpture is one among numerous exceptional works in the show. Some are on loan from public collections, such as UCLA’s impressive Fowler Museum, while nearly three-quarters are lent from important private holdings, among them the Bill and Ann Ziff collection in New York. The show’s chief drawback is the absence of a publication, neither catalog nor brochure, which seems a shame for such a notable, curiosity-inducing display.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles. Through July 9; closed Wednesdays. (323) 857-6000, www.lacma.org

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

MORE REVIEWS:

The clever conceptual riddles of Tatsuo Kawaguchi

It's bathroom art: Joel Holmberg's toilet portraits

Ben Vereen, Ronald Reagan and the travesty of blackface, potently remembered

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.