The Getty just announced its most important drawings acquisition in 20 years—and adds a ‘Surprise’

Barely five weeks ago, the J. Paul Getty Museum secured the purchase of Parmigianino’s “Virgin with Child, St. John the Baptist and Mary Magdalene,” painted around 1535-40. Late Renaissance masterpieces being hard to find, acquisition of the pristine painting, which had hung quietly in a British castle for more than 250 years, ranked as a major coup.

Now, the Getty is announcing that it is adding an extraordinary group of 16 Old Master and 19th century drawings to its collection. This purchase, topped by a superlative Michelangelo rendering of a mourning woman in pen and brown ink, is the most important drawing acquisition since the museum opened on a Brentwood hilltop 20 years ago.

“Transformative” is the fitting adjective being used by Getty Museum director Timothy Potts.

As if drawings in pen and ink, pastel, chalk and oil on paper by Michelangelo, Andrea del Sarto, Parmigianino (again), Rubens, Goya, Degas and 10 more were not enough, the museum is tossing in news of the simultaneous purchase of another major painting.

Jean-Antoine Watteau’s “The Surprise,” a small but widely celebrated panel painted three years before the artist’s untimely death at 36 in 1721, had gone missing for more than 150 years. Long presumed destroyed, it resurfaced to great fanfare in 2007.

Surprise, indeed.

The museum does not disclose acquisition prices. But today’s announcement, all totaled, would significantly exceed the $31.5 million believed to have been paid for the Parmigianino. The Watteau alone was on offer for more than $22 million in 2011, while the Michelangelo sold at auction in 2001 for $7.7 million and Andrea del Sarto’s “Head of Saint Joseph” for $8.5 million in 2005.

Apparently, the ongoing Wall Street rally has been good to the Getty, where the endowment currently stands at roughly $6.5 billion.

The Getty is acquiring all the works, drawings and painting from a single, unidentified British collection. According to a museum spokesman, export licenses have so far been arranged for all but four drawings.

Great Britain has the unfortunate habit of trying to block significant works of art from leaving its shores. An export license can be temporarily refused while a local buyer is sought to match an agreed-upon price.

“The Surprise” was temporarily denied a license six years ago. (Apparently that sale was withdrawn and the block was lifted.) The recently acquired Parmigianino painting was similarly blocked, but no British buyer was found and the Getty prevailed. According to a museum spokesman, the Watteau does not now face a hold.

“The Surprise” joins Watteau’s “The Italian Comedians,” circa 1720, at the Getty, acquired in 2012. Some have doubted the attribution of the latter unsigned painting — yet it’s so good, who but Watteau could have painted it?

No reservations, however, accompany “The Surprise.” Previously known only through a copy in the Royal Collection at Buckingham Palace, plus a contemporary black-and-white engraving, the much-admired work was spotted languishing in a country house by a Christie’s auction expert.

Set in a sunset landscape, the exquisitely painted composition shows a couple embracing while Mezzetin, a stock character from Italian commedia dell'arte, tunes his guitar nearby. Watteau invented the popular motif of the fête galante, or courtship party, but this is a strange, even somewhat disquieting example.

The amorous couple was adapted from a pair of dancers in an exuberant Rubens painting of a country wedding — although here their legs have been truncated so that the figures are seated on the ground. The aggressive aristocratic man leans in to land an almost violent kiss on the rather unreceptive lips of a woman dressed in peasant clothes, who turns her head aside.

Mezzetin, wearing a rose-colored jacket and breeches slashed with yellow, is painted in a flickering style derived from Anthony van Dyck. He is not yet serenading the couple, but instead stares at them as he idly tunes his instrument.

At the lower right, a dog — symbol of fidelity, an animal borrowed (in reverse) from an extravagant Rubens painting of the proxy marriage of Marie de’ Medici — witnesses the event, his body twisting as if in a double-take. A loaded scene of insistent affection and weighty anticipation, this particular fête seems rather less than galante.

It was one of two panels originally painted for the discerning Parisian collector Nicolas Hénin. (In a happy coincidence, the pendant, an aristocratic scene of musical languor called “The Perfect Accord,” is in the collection of the

The picture’s rediscovery is something of a theme for the Getty acquisition. Several works have only come into public view since the start of the new millennium.

The magnificent Michelangelo drawing of a grieving woman who hides her face behind the heavy folds of her cloak was famously found tucked into a rare book in the library at Castle Howard, just north of York, England, in 2000. It joins a double-sided sheet of Michelangelo sketches, most prominently a Holy Family, acquired by the museum in 1993.

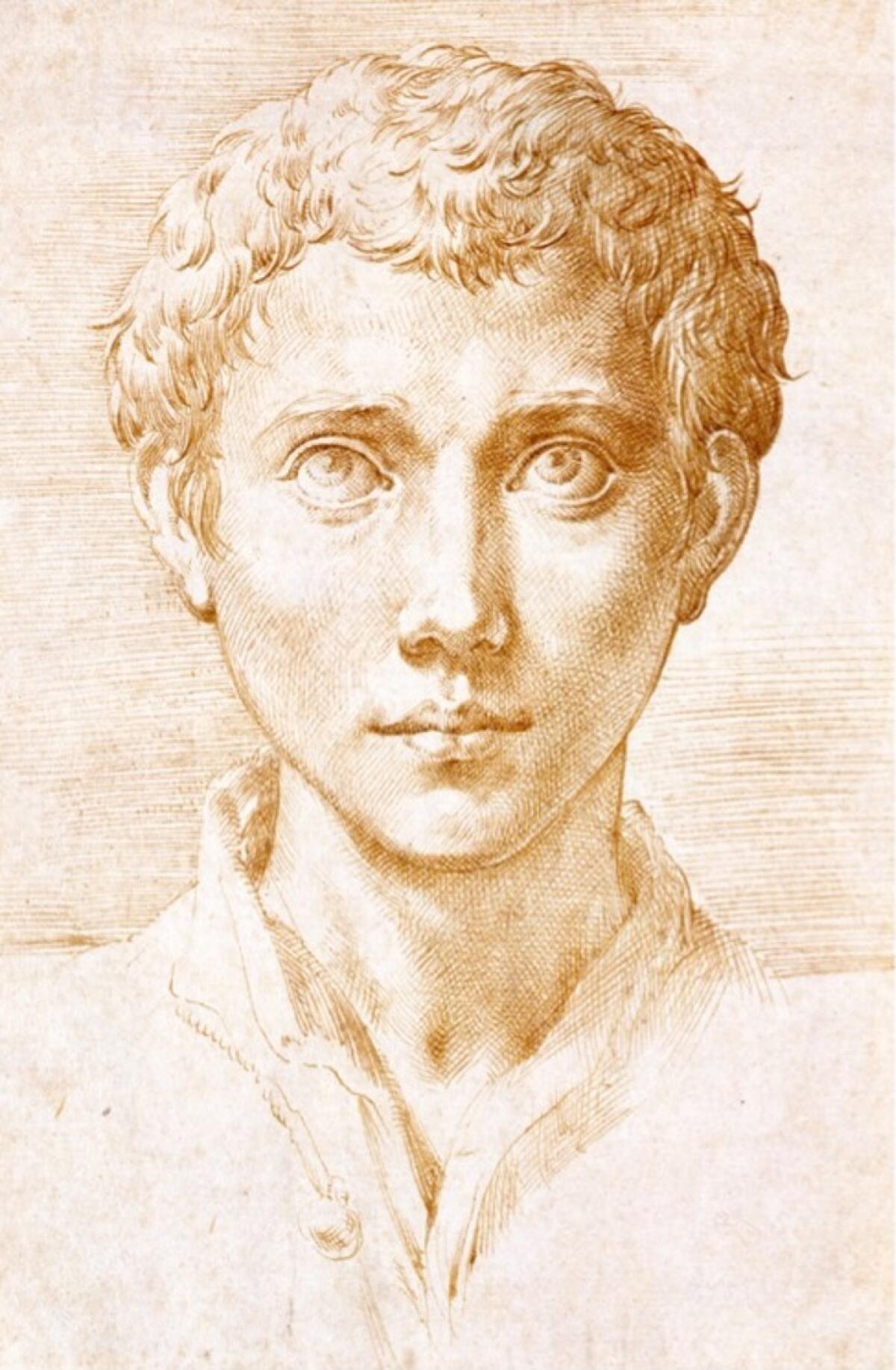

Parmigianino’s “Head of a Young Man” (circa 1539-40) turned up out of the blue in a Philadelphia collection in 2001. The stately if youthful head, rendered in hatched brown ink shaded with a flurry of dots, is fully frontal; but the boy’s disconcerting eyes are not. They are looking up, as if he’s scanning some unseen object hovering above the viewer’s own head.

.

The “Head of St. Joseph,” a study for Andrea del Sarto’s painting “The Holy Family” in Florence’s Pitti Palace, surfaced in a Swiss collection only in 2005. A vibrant mix of red and black chalk, the drawing was shown in a recent Getty exhibition about Sarto and Renaissance workshops. It once belonged to Sarto’s famous student, Giorgio Vasari, the first modern drawing collector and author of the landmark “Lives of the Artists.”

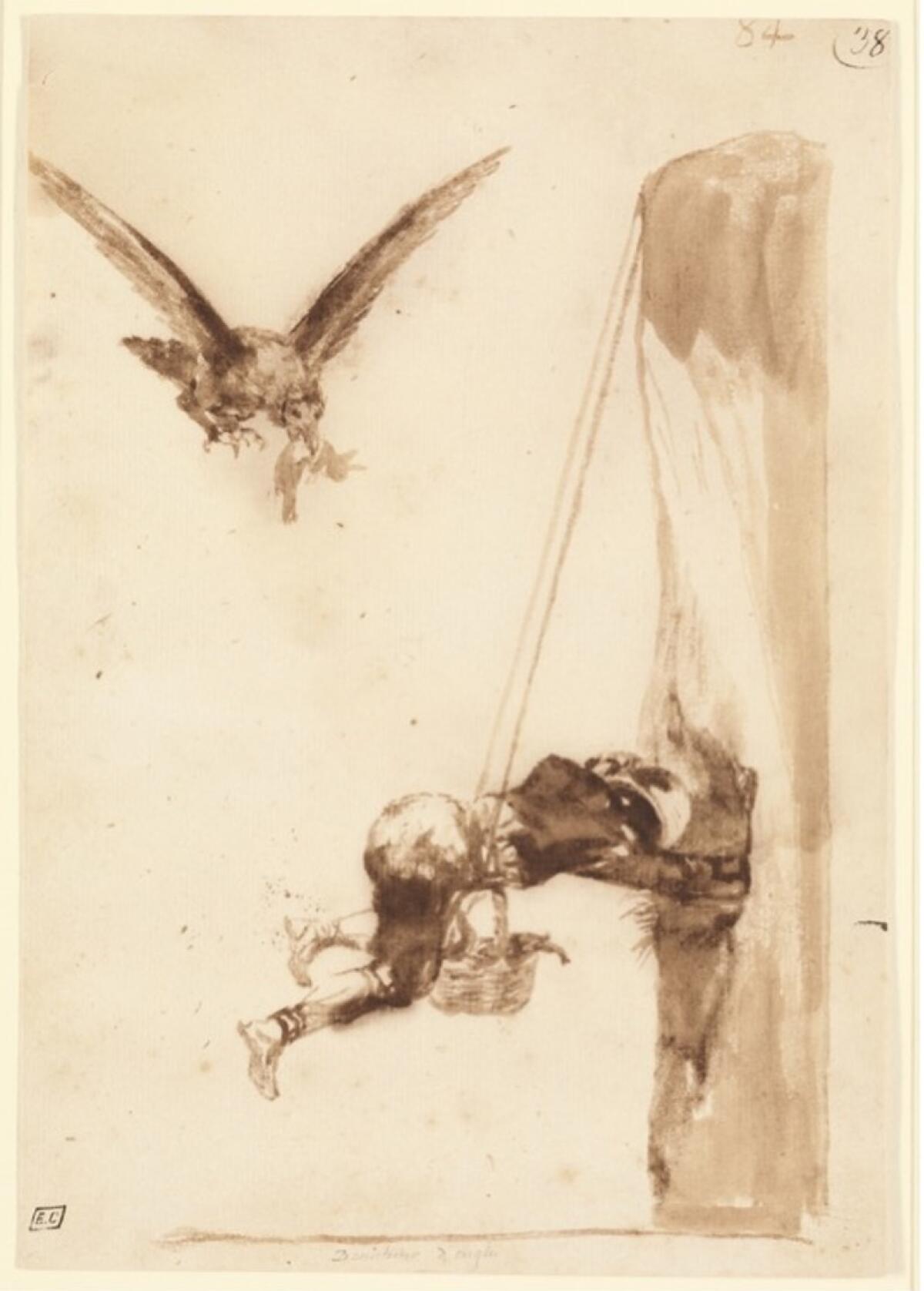

Ten of the 16 drawings are Italian, including works by Lorenzo di Credi, Fra Bartolommeo, Sebastiano del Piombo, Domenico Beccafumi and three more. They vastly improve the Getty’s Renaissance holdings. Others are by Aelbert Cuyp (Dutch) and John Martin (British), as well as Rubens (Flemish) and Goya (Spanish); and two are by Degas (French), including a large pastel of a bather, the theme of a major Degas painting in the museum’s collection.

The Getty plans to publicly unveil the new acquisitions together at an as-yet undetermined date.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

Nazarian family donates $17 million to CSUN's Valley Performing Arts Center

Review: Marisa Merz retrospective at the Hammer gives an overlooked female artist her due

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.